Non contenta l'Aquila di havere applaudito al suo Giove con l'Armi, volle anco ossequiarlo con le Lettere. [1]

In modern-day piazza Santa Margherita in the city of L'Aquila, still surrounded by some of the rubble left over from the 2009 earthquake, a recently restored white and solitary statue dominates and presides over the small empty square that is still part of the Red Zone.

The young master depicted is the Hapsburg king Charles II, which was installed in that small square with tenacity in 1675 by the Magistrato of L'Aquila, the city's governing body. The Magistrato strongly wanted to depict its adolescent sovereign, known instead for his illnesses, in full command of his Empire when he turned 14, therefore leaving puberty and entered into full control of his crown which until then was entrusted to his mother, Marianne of Austria.

Today, more than three centuries later, it now seems an important metaphor that symbolizes a posture of Charles II aspires to an ideal order despite his sickly and precarious body, and even then it was spectator, like the statue is today, of horizons that in reality lead to uncertain and complex paths.

That wholly baroque effort to represent the physical power of someone who was infact not physically strong, building around him an intricate tangle of symbols and political messages that were tools in support a precarious balance of power by aggrandizing the honor and obedience of a very loyal city.

Approssimandosi il giorno lietissimo del Cumpleanõs, e della Pubertà del Serenissimo Carlo II Rè delle Spagne" recita l'orazione dell'Accademia dei Velati all'Aquila, una delle Repubbliche delle Lettere più importanti del Regno, "si motivò dal zelo impareggiabile del Preside Don Emmanuel de Sesse, solennizzarlo con l'erettione di una Statua, onde la Fedelissima città dell'Aquila per avere avanti gli occhi il Simulacro del suo Natural Signore, che porta scolpito continuamente nel Cuore, prontissima concorse à secondare il motivo, e per maggiormente palesare il suo affetto, e ossequio […], risolse darne le seguenti dimostrationi, di Cavalcata, Accademia e Comedia". [2]

This passage synthesizes the entirety of the ceremonial language of apology for the sovereign's body, his rite of passage to adulthood, and the metaphor of his sovereignty, to stress the devotio of this city at the edge of the Empire. [3]

Multiple studies have highlighted the importance of the king's body in the symbolism of power and its representation in the baroque age, including the work of Kantorowicz, Bertelli, Visceglia, Benigno, Battistini, and Fagiolo. In the wake of these reflexions we can observe how the sculpture erected in L'Aquila that celebrates and depicts the body of Charles II is in realty testimony of sovereign power, in this case most fragile, of a young king, that still succeeds in showing a strong image through a multitude of interpretive codes and models that were in circulation at the time. The complexity of the evocative messages in the ceremony, which will be described below, renews the reflexion of the circularity of the communication and the characteristics of baroque culture.

The statue was placed in the square covered by a shroud until it was unveiled at the end of sumptuous cavalcade on the 6th of November:

Alle 21 hore del medesimo giorno, […] doppo essere state nette tutte le strade, recitata l'orazione dei Velati, e addobbata di stendardi la città, inizia la cavalcata. [4]

Il corteo, partito dal Palazzo Margherita, che portava appunto il nome di Margherita d'Austria figlia di Carlo V e governatrice della città tra il 1572 e il 1586, si diresse in un percorso originale verso i quattro quartieri nei quali fu fondata la città dell'Aquila nel 1254 e cioè quello di San Pietro [5], di San Giovanni, dove furono posti archi trionfali con scritte apologetiche e il terzo di san Giorgio dove fu eretto un Arco, "che nell'Eminenza haveva una Figura rappresentante Giove, che con la man sinistra careggiava un'Aquila, con la destra stringeva un fascio di Fulmini, con Elogij, e Aquile sostenenti Cartelle co' Motti adattati". [6]

The young Charles II, as a supreme Jove, who has caresses for the city and lightening bolts for his enemies. Continuing toward the last founding quarter of he city, that of Santa Maria,

si vidde l'ultimo Arco, con il Quadro nel frontespicio rappresentante la caduta dell'Esercito di Sennecherib, con Iscrittioni sostenute da altre quattro Aquile, e altri Elogij alludenti alle future Vittorie della Cattolica Maestà. [7]

A large crowd welcomed the procession in that game of popular participation that had contained, as was often the case in the ancien régime, the dilemma between popular passions and the real perception of symbols and messages. [8]

Therefore, once the procession finished taking political possession of the city by completing the itinerary of city's foundation, it then made its way to the Basilica of Saint Bernardino da Siena, in which the governor, the city's assembly, Nobility, and general citizenry, sang il Te Deum", followed by cannon shots from the Spanish Castle where the "Royal Standard was hoisted"; from which the cavalcade returned to Piazza del Palazzo where the Preside, after extensively praising the the nobility, ended the cavalcade ceremonially unveiled the statue of the king. [9]

The statue shows the young monarch portrayed with a baton and a globe engirdled with an ascending laurel at his feet, and the inscription on the pedestal is a dedication from the Governor, Emmanuel De Sesse, that says "EN CAROLI HISPANIARUM REGIS Simulacrum: Atavi nomine, ac omine Secundi, Nulli vero Secundi, D. EMMANUELE IOSEPH DE SESSE".

Promoting and hyping a monument to express fealty to a monarch as protection of the ruling dynasty was not new in the Kingdom of Napels. But it erecting statues of the young Charles II was unique because it appeared to happen mainly to remind the people, the subjects of the Spanish Crown, of the very existence and power of the sickly child monarch. In 1668 the Prince of Avellino, Francesco Marino Caracciolo, supported the building of a statue in that city. Made by Cosimo Fanzago, it depicts Charles II at the age of seven in regal and pompous attire. The same year that the statue in L'Aquila was erected, the Viceroy of Naples, don Pedro Antonio d'Aragona, financed in the quarter of Monteoliveto in Naples, a fountain topped off with a metal statue of the young king. A similar initiative to depict the child monarch's power also took place in the city of Capua.

The Governor of L'Aquila, Emanuele De Sesse, mas most certainly aware of these initiatives and, for this reason, wanted to include L'Aquila within the sphere of those who paid homage and expressed fealty to the Spanish Monarchy and the young king. It was a project that fell perfectly in line with the cultural models and initiatives that circulated in the Sixteen-hundreds. [10] But the uniqueness of these representations is not the obvious linearity of celebrating a sovereign, but rather the insistence on giving a vigorous body to the image of a child or adolescent monarch, who in reality was very sick and absent, as if they wanted to raise up, with corporal aspect of the sculptures, a body that was on the edge between life and death, to remind people of the weight of his importance and presence in those cities that declared themselves to be forever loyal to the crown.

The baroque monument in L'Aquila is the work of one of Bernini's students, the, Roman sculptor Marcantonio Canini, whose initials are concealed, but still visible, in the pedestal; build from white marble it is composed by the figure of the fourteen-year-old monarch dressed in armor with his word, a globe, and an expressive lion licking his right calf. [11] The pedestal is adorned with the coat of arms of the city of L'Aquila, a bird of prey, and governor de Sesse's shield.

The artist was well-known in Roman circles during the baroque period and he worked with the group of artists commissioned at the church of Sant'Agnese in piazza Navona, under the supervision of G. M. Baratta. With all probability he received the commission to build the sculpture for Charles II in the wake of his highly praised experience as a carver with his brother Giovanni Angelo. [12] The admiration he had acquired for his artistic capabilities was considerable if, at the death of Giovanni Angelo, in 1666, he was entrusted with completing the work his brother had stared called: Iconografia, cioè disegni d'Imagini de' famosissimi Monarchi, Regi, Filosofi, Poeti ed Oratori dell'Antichità , highlighting his extraordinary affinity thereof, for the entire body of culture of the emblems and devices that from Andrea Alciati [13] to Paolo Giovio, to Baldassar Castiglione and many others, characterized the figurative communication of the early baroque age. [14]

Marcantonio Canini, author of the sculpture in L'Aquila, affixed the legend for the images of Opera, already designed by his brother Giovanni Angelo. The Italian edition that he edited in 1669 was later translated into french under the title Images des Héros et des Grands Hommes de l'Antiquité (Amsterdam 1731), and distributed in France with engravings by B. Picart and J.-F. Bernard, as studied by Antonella Pampalone. The importance of his talent were evidently known in l'Aquila if the city's assembly decided to entrust the commission to him, an artist from Bernini's orbit, to build a sculpture representing the young king, endowing it with all the symbolic detail that derived from his composition of the text Iconografia in 1669, finished just a few years before Canini received the commission in l'Aquila.

The statue's unveiling took place on the exact day of Charles II's birthday, on November 6th 1675, at the end a splendid and princely cavalcade with which the city paid homage to the young king at the moment of his passage from puberty to adulthood, the climax of prestige for sovereign power.

The next day, not satisfied with the tributes given with the procession and the cavalcade, the city also wanted to pay homage with a polished literary recital of the young king's figure.

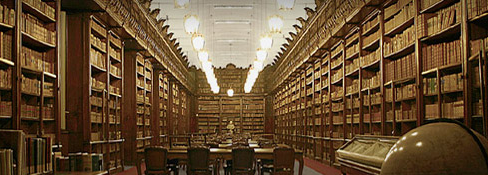

On November 7th, 1675, in a hall crowded with members of the Accademia dei Velati, the city's most important literary coterie and also one of the most notable in the south of the peninsula, to celebrate the Accademia, a collection of literary and poetic compositions for Charle II's the exit from puberty. [15] The published memoirs of these celebrations, strongly supported by the dean [preside] for the Province of Abruzzo Ultra [16], the spaniard Emmanuel De Sesse, were dedicated to the wife of Viceroy Fernando Fajardo Zuñica, Marquis of Los Velez, who had been nominated viceroy just two months earlier, substituting his predecessor Viceroy Antonio Pedro Osoryo on September 9th. Part of the peculiarity of this document is that the oration is not attributed to a specific author but is instead the work of many names within the Velati, and it does not carry a printing date but leaves observers to presume, from the writings of Ludovico Antonio Antinori, that it was published in 1675 by the L'Aquila-based publisher Pietro Paolo Castrati. Such a short period from the declamation in public to its publication induces us to imagine that its supporters wanted the opus to be published and promulgated with the upmost speed, giving even more visibility and distinction of this homage to the king in the city of L'Aquila and ensuring its rapid circulation in the most noticeable environments of the Spanish courts.

Of the four copies that are still traceable, two are in L'Aquila, one in Naples and the remaining one in Madrid at the Biblioteca della Complutense, a copy that was recently the object of scholarship by Conception Lopezosa Aparizio. [17]

In the Accademia dei Velati's hall, sumptuously adorned for the occasion with the symbols and emblems of the Spanish monarchy, the Velati's prince, Stefano Alfieri, spoke in front of the preside De Sesse, the auditor of the provincial tribunal, Bartolomeo Grisconio, the city's governing body (Magistrato), the bishop of Chieti, Nicola De Rodolovich, and other civic leaders and members of the Academy, to recite an oration in which he glorified the young king as the Spanish monarch, as he became now a proud commander of his Kingdom before whom both France and the Ottoman empire could only back away [18]:

Fermatevi Gallicane Falangi, le vostre per l'innanzi cotanto ardite Vele racchiudete dentro i patrij Lidi, tempo non è più di flagellar l'onde, all'acquisto di nuovi Stati, o Regni: […] e tu gran Corsare de' Mari, commune Tiranno, e del Popolo battezzato giurato Nemico, richiama, […] i tuoi sparsi Eserciti: […] è giunto già l'Austriaco Monarca a quegli anni, quando Giove, può a suo talento maneggiare i fulmini, e così atterrare il vostro Gigantesco ardire, […] è fatto già adulto il Sole Ibero, compare qual maggiore Luminare della Terra, che dunque aspettano i vostri Gigli, se non di marcire al riflesso della di lui luce, e di subintrare a perpetue eclissi […]: egli non tiene hora di latte humide le labra" […]. [19]

The reference to the kings age is repeated frequently, precisely to stress that this was the moment of his complete ascent to the throne, his assumption of command, and election as sovereign in every aspect. Baroque artwork enters in to politics, in the complexity and fragility of its equilibriums, trying not only to represent, but to transform, to resuscitate the fortitude of that which seems fleeting.

Once the initial declamation reached its conclusion, Stefano Alfieri continued the ceremony by opening it up to an internal contest of the members of the Academy, more specifically to observation of astrological symbols of the King and of Jove, that is of the Eagle and the Lion.

È l'Aquila ministra di Giove, e Depositaria de i di lui fulmini, vedesi altresì dotata d'occhio sì acuto, che schiva ogni periglio, s'avanza a vista del Sole: […]. È il Leone Primogenito della fierezza, terrore de' boschi, di natura, sì docile verso di chi supplichevole se gl'inchina, che invece di ferirlo, l'accarezza, l'ama quando dovria sbranarlo […]. [20]

In the dissertations that followed, the Velati's members compared the contrasting forces and symbologies of the eagle and the lion [21], and on which the participants declared themselves in favor of one or the other. At the end, preside De Sesse, concluded that if the Eagle is queen of the birds of prey and the birds, the Lion is the king of earthbound animals, towering of the young monarch, who was born under an earth sign.

In reality Charles II was born under the zodiac sign of Scorpio, which also has as its animal the Eagle, exactly like Jove does. The lion, therefore, would not actually be his astrological animal of reference. This symbolic forcing is a symbolic expedient for the the identification of Charles with Jove, both of them are king of kings, exactly as the lion is king of animals.

All the speeches by members of the Velati, therefore, contributed in that occasion to support the leadership of the Monarquía. However, they also called on France to join in the war against the turks with the exhortation «Volgi contro la Tracia il cuor guerriero a liberar l'incatenata Aurora». [22]

With these words, after laying down their writing instruments [23], the Velati ended the session of the Academy.

The subsequent occasions for celebration, most notably the wedding between Charles II with Maria Luisa d'Orléans, were also new opportunities to organize celebrations by the city of L'Aquila. For this marriage the Accademia dei Velati contributed with the oration of baron Annibale Palmario [24], which was also dedicated to the Viceroy of Naples Fernando Fajardo Zunica, marquis of Los Vélez.

While in the early years of the Academy's activities, specially the first half of the XVII century, its ranks included members, like the doctor Salvatore Massonio and the jurist Gerolamo Tartaglia, who dedicated themselves to purely entertaining poetic works, after 1648, subsequent to the Masaniello insurrection in Naples (1647) the Velati's the political commitment of the artistic production became, acclamatio, through works like La Laurea Austriaca by Antonio Alfieri [25], in 648, La Penna fedele del Pulci, in 1653, I Fulmini dell'Aquila, by Gerolamo Florido [26], in 1655,the Pentateuco by Alferi, and, in 1675, L'Augustissima Casa d'Austria, by Annibale Palmario. [27]

Moreover in those years a revolt in Messina broke out, with the consequent intervention of France on the island; it seams almost as though the city of L'Aquila wants contextually commit as compensation to the Monarquía for that "betrayal" with a double dose of devotion augmented by the extraordinary hurry to get the example of fealty and concordia ordinum to the printing press.

Already well before this oration,the city had already shown its loyalty to the crown when it dedicated, in 1658, ten days of sumptuous celebrations in honor of the birth of prince Philip Prospero, another son of Philip IV and heir to the crown, especially after the death at only seventeen years of age of Balthasar Charles then designated to inherit the throne. The celebrations lasted ten days because none of the city's institutions wanted give up their specific hegemonic role that might have been necessary if the lasted only one day: therefore the ceremonies were led by the city's governing body (the Magistrato) the first day, by the bishop on the second, by the castellan the third, by the Franciscan Observance of S.Bernardino on the fourth, and so on for ten days. [28]

As we know Phillip Prospero also died, in fact just a few months before the birth of Charles II. And it was probably for this reason that the last young Hapsburg was seen as an opportunity to aggrandize the Allegiance of the vassal City. Charles II, as we now know, synthesized in his chromosomes all the genetic anomalies that could derive from the inbreeding of the Hapsburg dynasty, to the point that geneticists are still studying him, for example in a recent article published by the Istituto di Genetica of the Facoltà di Biologia dell'Università di Santiago de Compostela. [29]

The ceremony here presented consisted in a cavalcade, the unveiling of the statue and the academic oration and had an apologetic significance, as highlighted in many passages of the declamation, to portray, as mentioned above, a real coronation of the King of Spain, who had just left puberty an assumed the command of his empire, at the end of the period of regency under his mother Marianne of Hapsburg. [30]

In l'Aquila, therefore, in this important piece of the mosaic of the Spanish Monarchy, in the works of sculptor Marcantonio Canini, a student of Bernini, and in the declamation of the Accademia dei Velati, we don't find just he paradigm of the sacrality of the king's body, but also the creation of a new body, in contraposition to that of a sickly young boy, which gave from and content to a sovereign who was destined to rule an empire of continents for a few more decades. A few years later this sculpture would be one of the few to survive the great earthquake of February 2, 1703 that devastated the city, rebuilt thereafter in the refined baroque forms of by Roman artists and artisans, like the architects Fontana, Cipriani, Fuga and Contini, whose work contributed to build the late-Baroque decoration that were later denied and often removed, which is the subject of a volume of the Collana del Barocco in Italia, edited by Marcello Fagiolo in 2011. [31]

Between the cavalcade, the statue's unveiling and the declamation, and the celebration of the emergence from puberty of Charles II, there is a melting pot of contradictions, conflicts and cohabitations that, even in their uncertainty, condensed the intellectual activism of the protagonists and movements of a dynamic society in which emerging cultural configurations were elaborating languages by following new sensitivities.

Notes

1. Biblioteca Provinciale L'Aquila (BPA) Accademia celebrata nella città dell'Aquila Per il cumpleaños, et erettione della Statua di S. M. C. Carlo II Re delle Spagne A'6 Novembre 1675. Con Relatione delle Feste antecedenti, e susseguenti. Dedicata all'eccellenza della Signora Marchesa de Los Velez Viceregina del Regno di Napoli. Sotto la direttione del Signor D. Emmanuel Giuseppe De Sesse Cavaliero Nobile del Regno d'Aragona dell'Ord. di Calatrava, Preside per S. Maestà della Provincia di Salerno, Delegato Generale per S. Ecc. della Campagna nelle Province di Terra di Lavoro, Salerno, Basilicata, Montefusco, Lucera, Contado di Molise, et in questa dell'Aquila Preside, e Governatore dell'Armi, Nell'Aquila, Per Pietro Paolo Castrati, 1675, p. 15.

2. BPA., Accademia celebrata […] cit., p. 7.

3. S. Mantini, L'Aquila spagnola. Identità, conflitti, convivenze (secc. XVI-XVIII), Roma 2009.

4. Accademia celebrata […] cit., p. 11: «Squadronato nella Piazza del Palazzo il Battaglione a piede, e fatto segno dalle Trombe, incominciò la marciata. Precedeva come Mastro di Campo il Signor Governatore della Città, con suo habito, e livree vaghissime;; seguiva, e serviva di Vanguardia una delle Compagnie a Cavallo, dove Comparve il suo Capitano, e Officiali con pompa non ordinaria d'habiti, (p. 12) di livree, Penne, adobbi di Cavalli, e altri militari ornamenti. […] Seguiva poi per Retroguardia l'altra Compagnia de' Cavalli, ove comparve il suo Capitano, e Officiali, con non dissimili, ma forse vantaggiosi ornamenti, così nelle proprie Persone, come nelle Livree, e Cavalli, li Soldati della quale spiccavano per l'uniformità delle Bande Rosse, con francie d'Oro, e i Cavalli riuscirono riguardevoli particolarmente per havere, oltre li altri adobbi, alla Groppa tutti una Scesa, seu Gualdrappiglia all'usanza di Raso rosso, sopravi ciascheduna l'Arma (p. 13) del suo Capitano; finimento, che portavano anco i Cavalli della prima, benché senza l'Arma sudetta".

5. Accademia celebrata […] cit., p. 13 «ove era eretto un'Arco asai riguardevole per la struttura, e per esservi nel quadro di sopra un'Arma di Sua Maestà attorno, e ne' luoghi delle Medaglie quattro Aquile Coronate, sostenenti la Cartella con il suo Motto, alludente all'osequio della Città, e grandezza Reale, sortovi altri Cartelloni con Elogij alludenti al medesimo".

6. Ibidem.

7. Accademia celebrata […] cit., p. 14.

8. S. Mantini, «Alli altri del vulgo lasciarete fantasticare col cervello»: letture e linguaggi dei cerimoniali rinascimentali in R. Mancini (ed.), La trama del tempo. Reti di sapreri, autonomie culturali, tradizioni, Roma, Carocci 2005, pp. 181-204.

9. Accademia celebrata […] cit., p. 15: "il signor Preside accoppiando le parti di Regio Ministro, con quelle di cortesissimo Cavaliere, doppo varie accoglienze fatte alla Nobiltà, si compiacque honorara con spendidissima Collatione, trionfando in ciò anche la sua Magnificenza. E sopragiunta in tanto la notte, si reiterarono i luminari alle Finestre con Torce, fuochi per le strade, suoni di Tamburi, e Trombe, e sparo di Mortaletti".

10. F. Cantù (ed.), Il linguaggi del potere. Politica e religione, Roma, Viella, 2009.

11. A. Leosini, Monumenti storici artistici della città dell'Aquila e suoi contorni: colle notizie de' pittori, scultori, architetti e artefici che vi fiorirono, Aquila, F.Perchiazzi, 1848, p. 108: "nel 1675 fu inaugurata a Carlo II Imperatore d'Austria e Re di Napoli, allorché uscì di pubere, la statua di marmo bianco, in cui è figurato il Re chiuso nella ferrea armatura […] un leone che umiliato e giacente gli lambisce il piede, ed il globo terrestre su cui attecchisce un ramo di alloro, e vien su a coronargli la spada: simboli di un gran Monarca, d'un vasto impero, e di guerreschi trofei". Nel piedistallo sono sculti gli stemmi del Marchese de Los Velez Vicerè di Napoli, del Preside dell'Aquila D. Emmanuele di Sesse, quello della nostra città, e di Carlo II. Il nome dello scultore è inciso sotto alla statua = W. Caninius Ro: Fecit.".

12. A. Pampalone, Marcantonio Canini, voce nel Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Treccani, p. 108.

13. Diuerse imprese accommodate a diuerse moralità, con versi che i loro significati dichiarano. Tratte da gli Emblemi dell'Alciato, in Lione, per Masseo Buonhomo, 1549.

14. P. Burke, Testimomni oculari: il significato simbolico delle immagini, Roma , Carocci, 2003.

15. "Pertanto il Giovedì 7 s'aprì l'Accademia de' Velati in una delle Sale maggiori del già detto (p. 16) Palazzo, residenza solita della Accademia quale stanza in quel giorno comparve veramente adobbata alla Reale, sì per li Drappi, che coprivano le pareti, sì anco per il numero grande de gli Elogij, Epigrammi, Anagrammi, Ode, & Imprese, trascritte in carte Imperiali a carattere grande all'uso, contornate da pitture con festoni, e Arabeschi, che con ordinanza pendevano da dette pareti, tramezzatevi molte corone di Lauro poste ad oro: componimenti tutti varij, uniformi però nell'applaudere a i Pregi di S. M. l'effigie del quale vedevasi in capo di detta Sala, sotto ricchissimo Baldacchino, sopra molti Gradini elevata, e da i lati doi Chori destinati per la Musica".

16. Accademia celebrata […] cit.

17. C. Lopezosa Aparicio, Memoria italo-espagnola de un aniversario real. Las fiestas en L'Aquila con motivo del decimocuarto cumpleanos del Carlo II in La traduccion en las relationes italo-espagnolas: lengua, literatura Y cultura, A. Camps (ed.), Editions Univarsitat Barcelona, Barcelona Hoepli, 2012, pp. 91-103.

18. L. Lopez, Accademie ed accademici, cit., p. 76.

19. Accademia celebrata […] cit., p. 17-21.

20. Accademia celebrata […] cit. p. 22: "[…] che potrà servirli per esemplare della più bella tra le virtù, che è la clemenza, maggiormente a pro di quei, che pria nemici, indi l'adorassero come sudditi, prerogativa per cui dichiararonsi sempre più grandi, esercitandola i Grandi della terra; dalla prima chi non havrà a predirli il possesso della Monarchia universale? […] la curiosità però Academica richiede di distinguere in qual delli due risieda in simile affare […] a chi devesi a lode di questa letteraria Pompa. Qui dovriano inserirsi le difese fatte dalle Parti dell'Aquila dal sig. Antonio Angelini, e di quelle del Leone dal signor Lorenzo Fonticola, quali (p. 23) per essere ambidue Accademici di somma eruditione, e talento, si cattivarono il plauso universale. Incolpane Lettore cortesissimo la strettezza del tempo, che non havendo permesso potersi dare alle stampe, ti priva di una delle parti riguardevole dell'Accademia".

21. Accademia celebrata […] cit., p. 23 «Cessino le contese, Signori, e diasi luogo ad un Personaggio cui devesi di vostra quiete l'honore, riveritelo, adoratelo, egli è il Cielo quell'occhiuto Argo del Mondo, che sa ben distinguere l'intrinseco delle cose, io (uditelo, che parla) così l'Aquila Reina de' volatili, come il leone Re degli Animali di terra, trassi qua su ad habitar fra le stelle, Regia soo de' Numi, e gli ammantai di luce, servendomi dell'una per una delle mie principali costellationi, per il principal segno del Zodiaco l'altro, e ciò perché riconobbi in loro eguale nobiltà, non dissimile chiarezza di sangue. Hora se all'essere corrisponde l'operare, ecco che da i due mentovati Soggetti posson prendersi sena divario gli augurij alle future fortune del vostro Austriaco Signore, ricordevoli delle gratie di vedersi degni Geroglifici della sua gloriosa Impresa, tanto è vero, se è vero, che le mie voci (p. 24) siano oracoli, chi altrimenti protesta, sappia che non parlo se non con lingue di fuoco, e di quanto dico l'osservanza sta riposta su la punta de' fulmini; diceva il Cielo».

22. Ivi, p. 80.

23. Accademia celebrata […] cit., p. 17.

24. BPA, L'augustissima casa d'Austria. Galleria historica della Pietà. Oratione detta nell'Accademia de'Velati nell'Aquila dal barone Annibale Palmarii Accademico Velato, dedicato all'eccellentissimo Sig. Fedinando Gioachino Faxardo Marchese di Los Velez Viceré di Napoli, Aquila, P. P. Castrati.

25. A. Alfieri, La Laurea Austriaca, Declamatione Accademica del Dottore Antonio Alfieri A. V. dedicata all'Eccellenza della Signora Marchesa de Los Velez Viceregina del Regno di Napoli, Aquila, P. P. Castrati.

26. G. Florido, I fulmini dell'Aquila fedelissima ministra del Gran Giove Austriaco. Risposta apologetica al Signor Conte Galeazzo Gualdo Priorato di Don Girolamo Florido nell'Accademia de'Velati detto l'Occulto, Aquila, Gregorio Gobbi, 1553.

27. L. Lopez, Accademie ed accademici, cit., p. 98.

28. S. Mantini, L'Aquila spagnola […] cit., p. 226-240.

29. The Role of Inbreeding in the Extinction of a European Royal Dynasty, Gonzalo Alvarez, Francisco C. Ceballos, Celsa Quinteiro, Departamento de Genetica, Facultad de Biologıa, Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, Santiago de Compostela, La Coruna, Spain, Fundacion Publica Gallega de Medicina Genomica, Hospital Clınico Universitario, Santiago de Compostela, La Coruna, Spain, Rivista "Plos One" nel 2009.

30. Bodart, Diane. H.: "Statues royales et géographie du pouvoir sous les régnes de Charles II et de Louis XIV" en Sabatier, Gérard y Torrione, Margarita (dir): "¿Louis XIV espagnol? Madrid et Versailles, images et modèles". Centre de recherche du château de Versailles. Édition de la Maison des sciences de l'homme, 2009.

31. S. Mantini, La scena della città: uomini, idee, rappresentazioni nell'Aquila barocca, in R.Torlontano, ed.by, Abruzzo.Il Barocco negato Collana dell'Atlante del Barocco in Italia, M. Fagiolo (ed.), Roma, De Luca Editori d'Arte, pp. 45-56.