The relic chapel in Kotor, where body of Saint Tryphon is kept, beside hundreds of relics of various saints, got its baroque appearance between 1704 and 1708. At that particular moment, the biggest part of the Bay of Kotor was governed by the Venetian Republic for more than 200 years, and therefore the chief sculptor of this reliquary, Francesco Penso Cabianca, came from Venice. Chapel treasures today dozens of silver reliquaries shaped like human arms, legs and busts, and many other made of wood and glass. During a long period of time, from XIV until XVIII century, these objects were often created by Venetian masters; however, the oldest were made by the hand of the local goldsmith of Kotor. The heart of this shrine was composed out of two reliquaries in which the body of the town's patron, saint Tryphon, has been kept ever since. Around these sacred objects a complex visual program was carefully designed.

This paper examines the ways in which this program influenced the perception of the 18th century beholders directed toward images of the sacred body. Reliquaries, as holly instruments of great importance for the fashioning of these images, will be observed as dynamic, ambiguous objects. Zivo Bolica Kokoljic, a very popular poet of the age, in one of his poems invites people of Kotor: "to your Tryphon now flee/ with dreadful tears and heavy cry/ to estinguish your flame that torment thee". [1] Here I will try to explain the complex relationship between vision and visual in the moment when quoted literal suggestion became a part of everyday practice of the contemporary believers.

Examination of the material, visual as well as archival sources, encourage me to propose answers to the questions such as: in which way people of Kotor visualize Saint Tryphon during their prayers? How they approached his holy presence in space? When the pious man looked at the reliquaries what he could see? Was there anything that denied his gaze? Or, translated into the language of visual studies: how did the physical structure of chapel's space influence the mental movement of the observer? Does the iconography of the particular elements of the reliquary become itself a dynamic category when it is joined with the gaze of the same observer? How did that gaze "look like", how was it"guided" in the specific context of baroque Kotor?

All these questions indicate the ways in which holiness was presented to the believer as an object, material entity. The aim of this paper will be twofold. First, I will try to present how the relic chapel acted as a whole, permanently active teatrum sacrum. On the other hand I want to emphasize the moment when a group of reliquaries became physically active in the town procession organized on Saint Tryphon's day.

Saint Tryphon's Marble Dwelling

In the year of 1667 a destructive earthquake damaged, beside numerous buildings in town, parts of Saint Tryphon's cathedral. The relic chapel was severely damaged, as well as the other churches in town which treasured reliquaries commissioned mostly by the members of confraternities. Over the following years the church authorities, accompanied by local nobility, tried to repair the damage caused not only by natural hazards, but also by frequent wars fought between Venetian Republic and Ottoman Empire.

Vicenza Buca, together with her husband Ivan Boliza, bequeathed in her last will the fund for the reconstruction of the chapel of relics in Saint Tryphon's cathedral, "without delay". [2] Only eleven days after her death a contract was signed between Venetian sculptor Francesco Cabianca and his new assistant Mafeo Torresini. [3] Archival documents reveal very little about the group of sculptors and stone carvers that worked with Cabianca. However, when it comes to Cabianca's presence in town, a preserved court document allows us to take a glance into his working days in Kotor. That note contains an accusation of the local priest, Tryphon Pasquali, for playing cards with the artist, despite bishop's prohibition. [4] In the year of 1708 Cabianca paid off his last assistant and, very soon, the relic chapel was consecrated, using the funds from the same will. New, marble "body" of the chapel hosted, once again, a group of reliquaries that had been creating during last three centuries.

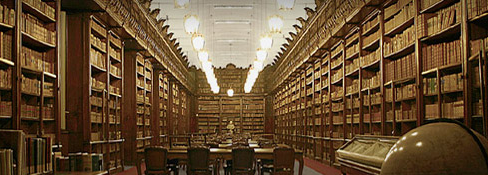

Before dealing with previously mentioned questions I want to introduce the particular elements of the Kotor's shrine. [fig. 1] Cabianca divided semi-circular space into the five niches, separated by columns and framed with the combination of red and white marble. Four niches became the spaces for keeping the reliquaries, and they were originally covered with silver. [5] The central part of the shrine treasured two reliquaries with the bones of the patron, as well as the reliquary of the True Cross. They were placed in the marble casket, held by two angels, with the figure of Saint Tryphon above them. In the lower zone relief plates tell us a story of torment and death of the patron saint, while, from the above, figures of angels are celebrating it with the musical instruments.

In 1745 bishop Castelli visited the chapel of relics and wrote: "The sanctuary is made of marble, wonderfully decorated with marble colons, and locked with three keys." [6] And indeed, when contemporary pious man had the chance to come up the great stone stairs, which alone had their role in creating the process of approaching this sacred place, the first thing that welcomed him at the top was a red iron grid. [fig. 2] The similar grid was mentioned in the descriptions that had been written decades before the reconstruction of the chapel. [7] However, instead of assuming that the reliquaries were hidden by it from the beholder, I want to emphasise how the believer's gaze was actually affected by its presence. In front of the grid Cabianca built a small altar from the same colourful red marble used in the space behind the fence. Here, the Mass was celebrated on particular days, and from this very place the viewer could look at the relics. In this paper I would like to propose what the beholder could see not only through, but with the mentioned grid. Every wider scene of this sacred space Cabianca supplied with light by choosing its sources carefully. [fig. 3] The whole inner space is accompanied with the four semi-circular windows, positioned in such manner it seams that light comes from the sky painted on the ceiling. Also, from the other side of the fence, a small round window provides light subtly but with strong effect, because the ray falls through the fence to the most sacred part of the chapel. [fig. 2] Moreover, this "heavenly" illumination is intertwined with yet another strong impression: the domination of red colour at the first sight. Strong dark red of the fence doesn't diminish in the space, but rather emphasizes the other hue of marble's red more lively, vividly and even more anthropomorphically. Being a background of a story that was narrated in front of the viewer, the red marble with its white details gives an impression of the body - sacrificed body and blood. Therefore, we can say that the pious observer, though unconsciously in the most part, and probably often not completely articulated, was stimulated by the contrast of light and material which gave the same colour twice - first as a symbol of the martyrdom, framing the entire sacred space, and second as a sort of presence, giving much more spontaneous impulse to the viewer's senses.

The whole structure of the chapel carried the same message to the beholder, transferred through multiple levels. From the moment when his gaze "entered", this sacred place became more eloquent and more ambitiously articulated. The centre of attention was (and still is) the sculptural group that guarded the relics of St. Tryphon. [fig. 4] However, in order for the beholder to perceive it as a truly essential, the entire space of the chapel had to be taken into account, because all its elements directed the gaze upward. This direction was particularly stressed with a triangular shape formed out of two figures of angels and St. Tryphon above them. Yet, the movement of the gaze was supposed to be experienced by the fateful viewer not just as physical, but as spiritual as well. Therefore, contemplation of the very space was necessary. The two rows of relief scenes at the base of the chapel show images of torment and death of St. Tryphon - in other words, they illustrate fundamental part of saint's vita, part that justifies the heavenly (i.e. upper) place of this holy martyr. Moreover, the two rows lead, in visual sense, toward the red marble stairs that "lift" beholder's eyes to the figure of St. Tryphon.

This large white figure slowly emerges from the red marble background and strives toward the sky. Without the expected tension and struggle typical for the Baroque age at first sight, this figure actually carries in itself the inevitable ambivalence, though in a subtle manner. Besides the mentioned contrast of the red background and the plainness of the figure's white marble, the believer was invited to perceive the similarity of his own posture with the, certainly much more glorious, bodily attitude of St. Tryphon. The saint is kneeling and praying, with his head slightly raised toward the sky, toward God. Moreover, we may assume without much doubt that the contemporary believer was also kneeling with his hands in the gesture of prayer and his gaze directed upward toward the saint's body. However, interconnection between the visual program and the pious viewer was not only expressed through corporal imitation of the later. For the contemporary fateful man St. Tryphon was present in two places at once - in the beholder's space through his bones in reliquaries, as well as through his marble figure; and in Heaven, invisible and inconceivable realm of divine mercy. This duality of presence, very carefully articulated after the Council of Trent, was subtly implied here. While kneeling on cloud, in the moment of spiritual commitment to God, which is expressed through the fixed gaze of the saint toward the (painted) sky, St Tryphon slightly lifts his knee. To the observer who has been led one step forward by every image, this movement may seem very eloquent. Being ever present, immortalized in stone, this movement actually confronts the very nature of the marble. It seems that saint is about to leave his pedestal any moment now, and finally arrive to his new dwelling. This very peaceful figure, together with its surroundings, is kind of subtle macchina eterna. [8] The impression is reinforced with the figures of angels on the top, who, with their instruments, celebrate this constantly repeated movement of soul.

However, there is one important question: what was the exact role of the reliquaries in this process? Beside the relics of St. Tryphon the remains of many other saints are treasured in the chapel, placed in the side niches. Among the reliquaries of various shapes, which also differ in their materials, the most prominent are the silver ones in the forms of arms, legs and busts. How were they perceived in the gaze of the believer in the beginning of the 18th century? What we can say with great certainty is that they were always seen as a group [9], as the integral part of the shrine. Furthermore, it should be noticed that while they were accessible to the eye of the contemporary beholder, he was not allowed to see the two most important objects - the reliquaries of St. Tryphon. Instead of the glass that we can see today on the casket held by the angels, once there was a silver panel, still preserved, yet removed from its original position. This may seem odd if we consider that the relic chapel of Kotor was built in order to house and praise the remains of this very saint. To understand this, once more, we have to turn our attention to the gaze of the contemporary viewer in its specific context.

Saint Tryphon's Silver Court

Reliquaries are extremely dynamic and independent objects. Without cultural milieu as well as legends and rituals, and above all without the observer's gaze, they remain passive and today often seen as bizarre and surprising parts of the past. We should bear in mind that the heart of this objects are bone, physical remains of the human corpse, the matter that required animation in any point in history. The placement of abstract particle into the holly container works as a basic mechanism of its animation. Reliquaries speak for the relics, although usually in metaphors. [10] Even labelling their speech as metaphorical can be, once again, a part of our time. It is more likely that the baroque observer didn not have a need to place that particular type of communication inside of any specific linguistic or mental borders. Nonetheless, once buried into the reliquary, the bone became inseparable part of it. Both elements together created the same sacred massage that obtained its complete shape through the participation of the beholder. Therefore, it is more accurate to imagine this communication as a circle of exchange between the causes and the effects, than as a just two-way process.

In the same manner as reliquaries were dependent and active, the gaze of the beholder had as its essence closely-knitted network of various learned and sensational impulses. For instance, in previous part of the paper I pointed out the way in which observer, most likely, approached the chapel's space. In spite of the social rank to which he belonged the faithful man could comprehend the very same thing, although in a different form: materiality can provide access to Heaven trough particular objects. Whether he prayed in front of the icon, reliquary-locket, a group of sculptures or the arm-shaped reliquary, concomitance was a habit of mind as C. W. Bynum pointed out in her book [11]. Sermons that had been delivered on the feast days, basic prayers that every participant was able to say during the Mass, as well as more formal education for the members of the wealthy families influenced the congregation to perceive chapel space in the particular way.

We may assume that much attention was given to the orthodox fashioning of the gaze of the true Catholic believers, especially in the period when, being unquestionable till that time, "concomitance" was seriously reconsidered, and not just by the Protestants. However, we should also keep in mind that the "orthodox gaze" didn't consist only out of quiet, peaceful prayer and passive meditation. People of Kotor wanted to participate actively in the life of "their" saint and his "heavenly fellowship"; they desired to touch the relics, to kiss them.

Even though they were not allowed to be touched, these reliquaries, displayed on shelves of the chapel, must have had the strong effect on the beholder. [fig. 5] Unbreakable chain made of silver arms, legs and faces, put one next to the other, must have had special place in the aforementioned sacred story. First, I would like to emphasise their great power as a group. Despite the fact that they were not made all at once, but from the 14th century onwards, they all possess certain significant similarities. They were all made of silver and in life-size dimensions of the human body - both important characteristics in order to transfer the sacred since the Middle Ages.

This fact, as well as the mentioned desire of the beholder, helped me consider these reliquaries shaped like arms, legs and faces as a single whole, instead of many individual pieces. [fig. 6 and 7] Accustomed to the idea of concomitance, people of Baroque Kotor were able to imagine this holy treasure, body parts of various saints, as the whole bodies of the "heavenly audience" that was ever watching the glorious moment of the ascension of St. Tryphon's soul. For the pious men and women of the 18th century this was the gilded, dynamic and truly present image of the Heavenly Court celebrating, with music of the (marble) angels, the arrival of its new courtier.

When writing about this martyr, poet from 17th century Kotor, Boliza often used a specific pictorial language. We can read in the beginning of the poem from the circle dedicated to churches of Kotor: "Oh, shield my dear and trustworthy", and in the end he named the saint "our knight sent from above". [12] In yet some other poems, even those not entirely religious, he wrote about St. Tryphon as God's gift "who was given as a guard to Kotor (town)", "the town that he defends with his knightly arms". [13] These distinct militant and knightly motives, clearly associated with the image of the patron saint, surely had to do with the unstable times when people of Kotor dreaded the potential attack from the Turks. However, the thing that interests me the most is how this verbal imagery was transmitted to others - often illiterate beholders.

According to one record there were four additional reliquaries of St. Tryphon in the chapel of Kotor, [14] beside those of saint's head and body - two were arm-shaped and two leg-shaped reliquaries. Why did the people of Kotor need "division" of their patron? This question actually confirms the previously mentioned desire of the beholder to see the part as a whole. Even during his life, the most active body parts of St. Tryphon were his arms and legs. [15] His miraculous powers were, in a way, dependent on them. While healing the faithful and exorcizing daemons the martyr used his wondrous hands, and when journeying on foot he was spreading his Christian marvellous deeds. After the hour of his physical death, the same body parts, renewed with silver and precious stones, were expected to continue with their previous miracle making. St. Tryphon was supposed to protect his people. Provided with many body parts of different saints, contemporary townsfolk could feel secure knowing that, if necessary, a heavenly army, clad in silver would come to their aid, while, on the other hand, the Church had in its possession the powerful "fist" of ecclesia triumphans. Exactly through their materiality, created out of silver, precious stones, glass, as well as light, and animated with deliberated rituals and numerous legends, the body part reliquaries encouraged the contemporary pious beholder to imagine them as knights in shining armour.

However, interpretation like this one imposes the question which stems from everything previously said: did the Church somehow encourage mental "finishing" of these holly objects? If so, why reliquaries were not created in the form of complete life-size figures, but as the images of its separated elements? Answering these questions can be a delicate task in regard to different circumstances of their making as well as the complexity of their function. Nonetheless, it can be possible, with the help of preserved sources, to indicate at least the ways in which Church influenced this issue.

It is important to emphasize that post-Tridentine Europe still wasn't the space of the constraint borders or prominent dualities. [16] In spite of numerous rules, often recognized as a part of the true doctrine which literate minority should pass on illiterate majority of believers, one should be careful when it comes to applying of this model on the local level. In this paper popular religion will be considered as a practical response, personal appropriation of doctrine, which could easily cross social boundaries. [17] Although it cannot be denied that differences between social strands existed during the early modern period, I want to underline the diversity of form instead of the content of the mentioned appropriation.

Questions about fragmentation and "finishing" of the reliquaries are closely related to the examination of the whole structure of the chapel. What Cabianca represented in the figure of saint Tryphon was the moment that immediately precedes eternity. We should bear in mind that for the beholder this figure acted as a substitute, explanation of what he wasn't able to see - of the reliquaries with the saint's body. The movement of the figure is about to happen, which is the characteristic that was often celebrated in Bernini's sculptures. That particular way of representing body is closely related to baroque comprehension of time, cosmic and individual, as well as to the complex examination of the somatic aspects of the human soul. For that reason, in visual representations this movement is depicted as a dramatic moment of passion, an ambivalent condition of soul accompanied by the image of the strained body. Cabianca did not do that. His figure is peaceful; whole "noise" of the moment is depicted through the subtle lifting of the St Tryphon's knee. Once again, believer was able to conceive only a part, eloquent part which should act as a trigger for the creation of the whole story. In this instance the wholeness is inconceivable, holy meeting with God can be presented only through the earthly language, through the symbol, allegory, or, in this case, by the effective interruption of the implied movement.

Here lies the reason for a persistent encouraging of the beholder's imagination to see the reliquary as a totality of the particular saint, while offered only with a particle of his bone. Reliquaries in the form of the human figure exist. However, it should be noticed that at least one of the earlier mentioned features of the holy is missing in those examples. For instance, Kotor's cathedral treasures' reliquaries of Saint Barbara and unknown saint. [fig. 8] made in the shape of the human figure, but of wood. Aside from not being made out of silver, their dimensions are significantly smaller than other life-size figures without relics inside. These mechanisms of transmission of holiness by imitating exact dimensions of the earthly body and by "eternalisation" of its parts in silver and gold are very important components of the sacred objects. I suppose that in this case can be useful to "invert" chain of thoughts: first to examine the reasons why something didn't exist in order to reach the motives for creating existing visual objects at the end. Therefore, at least for a moment, we can try to imagine the appearance of the reliquaries which would be able to transfer similar message in a more literate sense and without previously described stimulation of beholder's imagination. The silver "human" figure, full of jewels and glass and in life-size dimensions, probably wouldn't be a good choice for a container of the martyrs' bones in the early modern period, and here is a possible reason for that.

Post-Tridentine Church had made an effort to engage visual as a way to Heaven, to establish boundaries around question of concomitance, often used very creatively by the common laymen. The main concern of the Catholic Church was to protect a belief in presence of God in material (in host, image, as well as bone). On the other hand, this desire was often followed by the fear of the possible mistakes, of intertwining with idolatry for which was loudly accused. Nevertheless, it should be considered that the moment of Reformation is the only one, although loud and important, point in history of this relations between desire and fear, which can be traced at least from XI or XII century [18] (the same time when anthropomorphic reliquaries were becoming more popular). However, it was the time of Protestant Reformation when the problem of idolatry became more clearly articulated. We can say that if theologians of the previous centuries were often debated how materiality can embrace holiness, in the years after the Reformation same question had more often begun with whether. The great part of Northern Europe formulated its answer as negative, which had to have strong affect on Catholic Church. What I want to underline here is not the simple, automatic answer of the Catholic Europe to this rejection. More relevant task would be consideration of the common ground from which those questions grown. However, slowly but sure, the echo of these changes had became a part of Kotor's church. Strong belief in presence of the holly in images, along with the fear of radical utilization of this thought can be perceived as prominent parts of the fashioning physical appearance of the saints. Revered by the members of different social groups as extremely powerful objects, the reliquaries were often presented as a part (fragmented, reduced, artificial). If staged as life-size silver figures, with the authentic part of the saint in their "hearts", reliquaries could act as a triggers of the unwanted idolatry, very appealing (especially by the standards of Trent) to the common folk. Instead of that, the believer was encouraged to use these non-similarities as an instrument for the mental finishing of the sacred bodies, the same way as they could be found in Heaven. Similar "evocation" of Heaven can be recognized in using dry flowers, often placed into the reliquaries, right next to the bones.

Conclusion: Saint Tryphon's Holy Walk

The Church stimulated this "imagination". On February 3rd every year, special town procession was organized and all reliquaries of the chapel were its participants. [19] That was the day when every townsman could approach them very near, and even touch them. Timotej Cizila, educated Benedictine monk, had written about this event much before the renovation of the chapel. In 1624 he wrote: "People from the principality and many others usually bow deeply to the saint's head kissing it humbly, and then they wipe it and clean it with the white cotton cloths that hang on the little thick candles. Afterwards they keep them (cloths) with great care, piety and devotion until the moment of their death." [20] This precious testimony tells us that once a year the mentioned pious beholder actually had his chance to fulfil the desire of taking active participation in the sacred, even making part of it his own personal property. These candles, we may say, became the contact relics. Therefore, we should bear in mind that denying access to the reliquary of the saint's head, placing it behind the silver plate in the chapel, was strongly related to its temporary "presentation" to the beholder. The power of the accessibility of the reliquary actually depended on its unapproachability. Cizila also described the whole ceremony, whose mentioned "encounter" was just its final part. He wrote about a grand procession, in which many people followed the body of their patron saint, as well as "the relics of saint martyrs that number 38, covered with silver and adorned, and among which were heads, arms, busts and feet." [21] Therefore, once again, these objects represented a group even in movement - a powerful silver fellowship of St. Tryphon, whose head, on this occasion, was carried by the bishop. Furthermore, not only church, but the representatives of the civil and military authority had their carefully determined place in this procession too. Thus was the relationship between the heavenly and earthly hierarchy projected before the eyes of the contemporary beholder, giving him chance to observe and question the quality of these relations. [22]

However, this impression had one more "contributor". The day before the procession, on the 2nd of February, the relics of all churches of Kotor were brought into the cathedral. We also know from the sources about the town disputes, concerning this matter, that were resolved only after the bishop had determined the order in which relics from all over the town entered the church. In the cathedral's account book we can find the description of how the interior of the church was decorated for that occasion: "beside silver and precious carpets, many candles were lit on sides, on the altars, especially on the main one". [23] The relics, placed on each alter, were censed during the morning service and "Lauds". In this ceremony six noblemen and six townsmen took their part, while the marine representatives were included as the "ceremonial guard". [24] Once more, the balance between the big and small was before the eyes of the pious beholder.

In the end, I would like to conclude that the baroque viewer was ever encouraged to fashion the dynamic image of the sacred in his own imagination. This imagination was, of course, the product of his contemporary experience and attitudes. A part, holy element crucial in this process is the reliquary. The question why that particular object, by its morphological structure, triggers a particular answer from the beholder is a very complex one, and it probably exceeds the limits of this paper. However, it is important to indicate at least motives and manners of the encounter between two participants of this (sacred) process, between physical and mental image. That is the main reason why the the encounter between the viewer and the reliquaries shaped like arms, legs and busts is of special importance, as well as the denial of access to the two most important reliquaries in the chapel. In this paper I tried to reconsider at least some of the rules of this saintly "game" that carries as its utter source the visuality.

Images

1. Francesco Penso Cabianca, St Tryphon's relic chapel, Kotor, 1704-1708

2. St Tryphon's relic chapel, Iron grid

3. St Tryphon's relic chapel, Semi-circular windows

4. St Tryphon and angels, Saint Tryphon's relic chapel

5. Arm-shaped reliquaries, XIV-XVII century, St Tryphon's relic chapel

6. Body-part reliquaries, XVII, XVIII century, Saint Tryphon's cathedral

7. Wooden reliquaries of St Barbara and unknown saint, St Tryphon's cathedral

8. Head reliquary of St Tryphon's, XV-XVII century

Notes

1. Živo Bolica Kokoljić. Pjesme, ed. Miroslav Pantić, Književnost Crne Gore od XII do XIX vijeka Cetinje 1996, p. 196. I am grateful to Jakov Đorđević for translating the verses discussed in this paper.

2. For the transcript of the Vicenza Buca's will see: M. Milošević, Pomorski trgovci, ratnici i mecene. Studije o Boki Kotorskoj XV-XIX stoljeća, ed. Vlastimir Đokić, Belgrade-Podgorica 2003, pp. 464,465.

3. Ibid, 267.

4. Historical Archive Kotor, IAK SA CXXX, 587, transcription in: M. Milošević, Pomorski trgovci cit., p. 267.

5. For the transcript of description of the chapel by bishop Castelli see: I. Stjepčević, Katedrala Svetog Tripuna u Kotoru, Split 1938, p. 22.

6. Ibid

7. Ibid

8. The baroque concept of bel composto is discussed in: : G. Careri, "The Artist" in: Baroque Personae, ed. R. Villari Chicago 1995, pp. 290-314.

9. Cfr. C. Hahn, Strange Beauty. Issues in the Making and Meaning of Reliquaries, 400-circa 1204, University Park 2012, p. 12, 13.

10. The question of the relationship between relic and reliquary is discussed in: C. W. Bynum, P. Gerson, "Body-Part Reliquaries and Body Parts in the Middle Ages", in Gesta, Vol. 36, No. 1 (1997), pp. 3-7; B. Drake Boehm, "Body-Part Reliquaries: The State of Research" in Gesta, Vol. 36, No. 1 (1997), 8-19; C. Hahn, "Methaphor and Meaning in Early Medieval Reliquaries", in Seeing the Invisible in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, G. de Nie, K. F. Morrison, M. Mostert (eds.), Utrecht 2005, pp. 239-263.

11. C. W. Bynum, Christian Materiality: An Essay on Religion in Late Medieval Europe, New York 2011, p. 213.

12. Živo Bolica Kokoljić. Pjesme, cit., p. 163.

13. Ibid, 208, 355.

14. I. Stjepčević, Arhivska istraživanja Boke Kotorske, Perast 2003, 45.

15. On this point see: C. Hahn, "The Voices of the Saints: Speaking Reliquaries" in Gesta, Vol. 36, No. 1 (1997), pp. 20-31.

16. J. J. Martin, "Renovatio and Reform in Early Modern Italy", in Heresy, Culture and Religion in Early Modern Italy. Contexts and Contestations, R. K. Delph, M. M. Fontaine, J. . Martin (eds.), Kirksville 2006, pp. 1-16, S. Ditchfield, "In search of local knowldge". Rewriting early modern Italian religious history, Cr St 19 (1998), pp. 255-296.

17. S. Ryan, "'The most contentious of terms': Towards a New Understanding of Late Medieval `Popular Religion'" in Irish Teoogical Quarterly 68 (2003), pp. 281-290.

18. Cfr. C. W. Bynum, "The Sacrality of Things: An Inquiry into Divine Materiality in the Christian Middle Ages" in Irish Theological Quarterly 78(1), pp. 3 -18.

19. The relations between baroque procssions and town is disscused in: Saša Brajović, U Bogorodičinom vrtu. Barokna pobožnost i Boka Kotorska, Beograd 2006, pp. 275-294.

20. Church archive Perast, Timotej Cizila, Bove D'Oro, NAP R XVI (56).

21. Ibid.

22. Cfr. P. Brown, The Cult of Saints. Its Rise and Function in Latin Christianity, Chicago 1981, p. 63.

23. Historical Archive Kotor, The Book of Accounts of the Kotor's Cathedral, KR II, 172, translated in: I. Stjepčević, Katedrala Svetog Tripuna u Kotoru cit., p. 55.

24. Ibid.