Stephanie Leone (ed.), The Pamphilj and the Arts. Patronage and Consumption in Baroque Rome, The McMullen Museum of Art, Boston College 2011.

Il libro curato da Stephanie Leone di cui, per gentile concessione della curatrice riproduciamo qui l'indice e l'introduzione, arriva al cuore della Roma barocca che è contemporaneamente un centro di cospicous consumption e una maglia di famiglie che creavano una fitta trama attorno alla Curia pontificia all'interno della quale operavano attraverso i cardinali e le varie fazioni. Senza traffiggerlo e meno che mai deturparlo vi giunge attraverso una serie di chiavi di lettura piene di significato: il mercato dell'arte, il patronage musicale, gli interessi scientifici, la politica delle alleanze familiari, gli equilibri del Sacro Collegio, le complesse dinamiche del prestigio e della distinzione.

I saggi restituiscono la centralità della figura di Benedetto Pamphilj, il quale, a sua volta, eredita una preziosa vocazione al patronage artistico, architettonico, musicale e culturale dagli altri membri della sua famiglia.

Benedetto, per usare l'efficace termine utilizzato da Leone, è un "poliglotta culturale"; è collezionista di dipinti, di oggetti (carrozze, orologi d'argento e strumenti scientifici) che danno il segno della distinzione e del prestigio di un membro illustre della sua famiglia e di una cardinale della Chiesa di Roma, accumulatore, restauratore e appassionato collezionista di libri, mecenate musicale e organizzatore di banchetti e di feste, anche collegati alle rappresentazioni teatrali. Quest'ultima è una forma di mecenatismo, indubbiamente più collegata ad aspetti materiali, quali il consumo di cibo e la prodigalità nelle feste, di quanto non poteva essere un'aria in musica, ma non meno pregna di significato, come hanno dimostrato tra gli altri gli studi di Renata Ago sugli arredi degli interni dei palazzi romani e la preparazione del cibo nelle varie occasioni di socialità e le ricerche di Martine Boitieux sul linguaggio figurativo e l'efficacia rituale nelle cerimonie della Roma barocca.

Benedetto manifestò anche un'attitudine all'architettura e soprattutto una chiara propensione a spendere in edifici, vocazioni entrambe direttamente ereditate dai genitori (Camillo Pamphilj e Olimpia Aldobrandini) ma che non erano neanche estranee alla trasformazione di Piazza Navona operata dal prozio Innocenzo X e dalla nonna Olimpia Maidalchini, di cui Stephanie Leone si è già occupata nel suo libro del 2008 su Palazzo Pamphilj a Piazza Navona.

Benedetto Pamphilj fu anche pastore arcade, altra chiave di accesso al mondo intellettuale e all'ambiente curiale romano.

Proprio questi suoi caledoscopici interessi e gli ambienti con cui entrò in contatto fanno luce sulle dinamiche culturali e politiche di Roma barocca. Porsi di fronte al quotidiano del committente e dell'artista, guardare alla mediazione attorno al gusto individuale e collettivo, studiare le trasformazioni del lavoro artistico è un primo passo per entrare nel mercato dell'arte. Ma volgere lo sguardo agli altri oggetti che il committente - Benedetto in questo caso - accumulava (mobilio, suppellettili di pregio, libri rari) significa entrare nei meccanismi dei consumi culturali, nelle dinamiche del collezionismo e alla costruzione di luoghi dedicati a tutti questi oggetti, aspetti su cui, in diverso modo i saggi del volume si soffermano. (Benedetta Borello)

Table of Contents

Preface

Acknowledgments

Stephanie C. Leone, Introduction

Maria Grazia d'Amelio and Tod A. Marder, The Four Rivers Fountain: Art and Building Technology in Pamphilj Rome

Catherine Puglisi, The Aldobrandini Lunettes: from Early Baroque Chapel Decoration to Pamphilj Art Treasures

Andrea G. de Marchi, Cannocchiali Pamphilj per le stelle, i quadri e tutto il resto,

Laura Stagno, Committenze artistiche per il matrimonio di Anna Pamphilj e Giovanni Andrea III Doria Landi (1671)

Carolyn Gianturco and Eleanor F. McCrickard, Notes on Alessandro Stradella, L'avviso al Tebro giunto

Alessandro Stradella, L'Avviso al Tebro giunto, (Once Tiber had been apprised)

Paul F. Grendler, The Jesuit Education of Benedetto Pamphilj at the Collegio Romano

James Weiss, "Too Much a Prince to be but a Cardinal": Benedetto Pamphilj and the College of Cardinals in the Age of the Late Baroque

Stephanie C. Leone, Cardinal Benedetto Pamphilj's Art Collection: Still-life Paintings and the Cost of Collecting

Daria Borghese, Cardinal Benedetto Pamphilj and Roman Society: Festivals, Feasts, and More

Stefanie Walker, Benedetto Pamphilj's "Sunflower" Carriage and the Designer Giovanni Paolo Schor

Alexandra Nigito, Le conversazioni in musica: Carlo Francesco Cesarini, virtuoso di Sua Eccellenza Padrone

Ellen T. Harris, Pamphilj as Phoenix: Themes of Resurrection in Handel's Italian Works

Laurie Shepard, The Power of the Word in Papal Rome: Pasquinades and Other Voices of Dissent

Alessandra Mercantini, "Fioriscono di splendore le due cospicue Librarie del signor cardinale Benedetto Pamfilio": studi e ricerche sugli Inventari inediti di una perduta Biblioteca

Appendice

Alessandra Mercantini, La perduta Biblioteca del cardinale Benedetto Pamphilj: Acquisti, rilegature e restauri

Vernon Hyde Minor, Cardinal Benedetto Pamphilj as Felicio Larisseo and the Arcadian Academy in Rome

313 Plates

Stephanie C. Leone, Introduction

This international, interdisciplinary, and collaborative project has been a long time in the making and has evolved through iterations. The idea was born in 2002, from interests about art collections, galleries, and Rome shared by Daria Borghese, Nancy Netzer, and me. We started to conceive of an exhibition about the practice and meaning of collecting in Baroque Rome, as told through the story of the Galleria Doria Pamphilj, a privately owned museum in Rome that houses the works of art collected by the Aldobrandini, Pamphilj, and Doria families.1 The idea was a natural fit for the McMullen Museum of Art at Boston College given the inherent connections between the Jesuit identity of the University and the early modern city of Rome. When we proposed the idea to the Pamphilj heirs, Don Jonathan Pogson Doria Pamphilj and Donna Gesine Pogson Doria Pamphilj and her husband, Massimiliano Floridi, they responded with enthusiasm. While developing the theme and content of the exhibition, we brought into the conversation the scholars who best know the Pamphilj collection and archive: Andrea G. De Marchi, then curator of the Galleria Doria Pamphilj, and Alessandra Mercantini, Director of the Archivio Doria Pamphilj. Dr. De Marchi deserves credit for focusing our attention on the patron and collector Cardinal Benedetto Pamphilj (1653-1730), who had not yet received the amount of scholarly attention his patronage activities merit. He proved to be a fertile subject, one that allowed us to fulfill the goals of the McMullen Museum: augmenting scholarship, generating faculty research, and encouraging scholarly collaboration.

About a year before the exhibition was scheduled to open in 2010, we learned that the Italian Ministry of Culture had recently denied loan requests from the Galleria Doria Pamphilj. When it became clear that the necessary permissions would not be granted, we decided to postpone the exhibition. Though disappointed, we shifted our focus to salvaging the research efforts of the contributing scholars, whose number had grown to fifteen, and transformed the exhibition project into a conference, which was held at Boston College in October 2010. The conference provided a valuable opportunity for the participants to exchanges ideas with one another as well as with members of the audience. These interactions improved the results of our research, and it is the revised papers that are presented in this volume.

The Life of Cardinal Benedetto Pamphilj

Cardinal Benedetto Pamphilj-a veritable cultural polyglot-circulated at the heart of the city of Rome in the last third of the seventeenth and the first third of the eighteenth century.2 He was born in 1653 into the top echelon of the social hierarchy of Rome. At the time of Benedetto's birth, his great-uncle Innocent X (1644-1655) was the reigning pope. The election had catapulted the Pamphilj to the apex of the city's social, political, and religious hierarchies. Innocent X commissioned works of art and especially architecture to articulate his new status, while avenues of power and wealth opened to his family. Like his predecessors, the Pamphilj pope, seventy years old at the time of his election, sought to situate his relatives firmly among Rome's nobility before his demise. Bendetto's father was Camillo Pamphilj, at first cardinal nephew to Innocent X and then secular prince, when in 1647 he renounced the cardinal's hat and married Princess Olimpia Aldobrandini Borghese. Benedetto's mother could boast more celebrated credentials than her husband: She was the descendant of Clement VIII Aldobrandini and the widow of Paolo Borghese, a relative of Paul V. As the last surviving heir of her family, Princess Olimpia inherited the Aldobrandini patrimony, which included Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini's renowned collection of Old Master and early Baroque paintings and his palace on Via del Corso. Camillo Pamphilj became a serious art collector in his own right, the first in the Pamphilj family. At the Palazzo Pamphilj al Corso (formerly Palazzo Aldobrandini) Camillo and Olimpia hosted concerts, theatrical performances, banquets, and other entertainments for the nobility of Rome, and in turn, the couple frequented the city's learned academies, including the celebrated Accademia reale of the famed convert Queen Christina of Sweden (1626-89). This is the world in which the young Benedetto grew up and in which his parents, especially his mother, nurtured him to become a learned and sophisticated nobleman.

Cardinal Pamphilj has been called "a perfect man of the Church," a sobriquet that aptly reflects his service to the Church and his patronage of the arts.3 According to the customary practice of Roman noble families, as the second son Benedetto was destined for the Church and was groomed to fulfill this role. For a man of his pedigree, this position in society combined the qualities and duties of nobleman and ecclesiastic. The young Benedetto's formation in the cultured atmosphere of the Palazzo Pamphilj al Corso was coupled with a formal education at the most prestigious school in Rome, the Jesuit Collegio Romano, which rested opposite the family palace on Piazza del Collegio Romano. After years of study, Benedetto earned his doctorate in philosophy and theology in 1676, and as was expected of a graduate with his credentials, he was awarded the cardinal's hat in 1681, taking holy orders three years later. Pamphilj served the Church as Grand Prior of the Knights of Malta, papal legate to Bologna, superintendent of the Port of Anzio and the aqueduct of Civitavecchia, protector of the Collegio Clementino, and archpriest of Saint John Lateran.

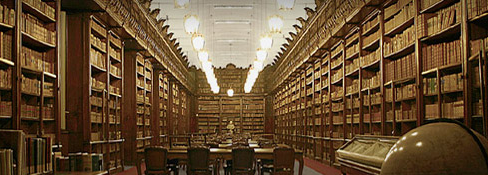

Cardinal Pamphilj dedicated himself to the arts. Music was his greatest love, and he was a central figure in the patronage of music in Rome. He supported the most talented musicians, among them Arcangelo Corelli (1653-1713), Alessandro Scarlatti (1660-1725), and George Frideric Handel (1685-1759), three names that have become synonymous with the birth of Baroque music. Furthermore, Pamphilj collaborated with musicians, writing lyrics for oratorios and cantatas that they set to music. And he hosted accademie musicali involving numerous composers and musicians beyond the names that resonate today. His interest in the literary arts gained him membership in the most notable society of literati in eighteenth-century Italy, the Arcadian Academy, whose members took poetic pseudonyms, read and wrote poetry, and acted in theatrical productions that sought to rekindle the imaginary, idyllic world of ancient Arcadia. From 1704 until his death twenty-six years later, Pamphilj's passion for books acquired an official role as cardinal protector of the Vatican Library and Archives. And through copious book collecting, he amassed two extensive private libraries, one of a general nature and the other of legal books, housed in the family palace on Via del Corso.

Cardinal Pamphilj was also a patron of the visual arts, including architecture, sculpture, painting, the decorative arts, and ephemera. Throughout much of his life he was occupied with building, maintaining, and renovating his properties, especially his apartment in the Palazzo Pamphilj al Corso, his villa outside the Porta Pia, the seat of the Knights of Malta on the Aventine Hill, and his country estate at Albano. To embellish these residences, he amassed a collection of about 1,400 paintings, most of which represented the minor genres of landscape, still life, battle scenes, and genre scenes. In addition to collecting paintings, he acquired what we call the decorative arts: carriages, silver, clocks, furniture, and other precious objects. Cardinal Pamphilj retained a house architect to oversee his building projects; Carlo Fontana, the most prominent architect in Rome after Gianlorenzo Bernini's death, occupied this post for three decades. Fontana built a theater and library in the cardinal's Roman palace to host his passions for, respectively, performances and books. The ephemeral entertainments of the theater extended to the elaborate banquets and refreshments-delighting the senses of sight and taste-hosted by the cardinal in Rome and the countryside.

Although many of his projects concerned his own properties, Cardinal Pamphilj also sponsored works at communal sites under his protection: the Collegio Clementino and, most importantly, Saint John Lateran. The realization of the sculptural program for the nave of the Lateran was the most important sacred art commission of the early eighteenth century. Over a half century before, Innocent X had commissioned the rebuilding of the cathedral's nave, under the architect Francesco Borromini, but the statues for Borromini's niches had never been realized. As archpriest of the Lateran, Cardinal Pamphilj fulfilled the promise of his great-uncle, overseeing the group of patrons who sponsored individual statues. Pamphilj himself commissioned the statue of St. John the Evangelist from Camillo Rusconi, and he gave a generous donation for the façade of the basilica, which was not realized, however, until after his death.

These are among the major events and activities of Cardinal Pamphilj's life as told by Lina Montalto over a half-century ago.4 Montalto mined the documents in the Archivio Doria Pamphilj to reconstruct Pamphilj's biography with great specificity, introducing the hoards of people who populated his world and the vast material culture that filled it. She looked high and low, describing the elite social circle in which he circulated and the luxury objects he possessed, along with the behind-the-scenes figures, such as staff members, merchants, and artisans and the purchase of essentials, such as bread and other foodstuffs. In studying the history of collecting and taste, albeit through one subject, Montalto was ahead of her time; her monograph was published eight years before Francis Haskell's seminal Patrons and Painters.5 Although Montalto's monograph has not exerted the same degree of influence as Haskell's broader study, it remains a fundamental source on our patron and the history of Pamphilj patronage. Nevertheless, it was time to reevaluate Cardinal Benedetto Pamphilj and to examine his activities within the critical perspective of patronage studies, as they have evolved over the past fifty years. In the compartmentalized academy of today, the cultural endeavors of Cardinal Pamphilj span disciplines. Until now, musicologists and art historians have been the scholars most interested in his story. In the early modern period the arts enjoyed a more interconnected relationship, and it was not unusual for a patron to have his fingers in the musical, literary, and visual arts. Such were the activities of a well-heeled and educated person. Today, the study of our patron's activities demands an interdisciplinary approach; to achieve this perspective, we assembled a team of specialists from the disciplines of art history, history, theology, musicology, and literature.

An Overview of the Essays

This study opens with three essays that address the patronage or collecting activities of Cardinal Pamphilj's ancestors, respectively his great-uncle, his father, and his mother. In the first, Tod A. Marder and Maria Grazia d'Amelio reconsider one of Innocent X's major commissions, the Four Rivers Fountain by Gianlorenzo Bernini. In dispensing with the traditional iconographic approach to its interpretation, they reexamine the fountain through the lens of technology. Using building documents, drawings, and other primary evidence, Marder and d'Amelio reconstruct Bernini's ingenious technical solution to executing "the monumental four-legged support whose surfaces were made to look like they have been yanked abruptly from the earth itself."6 They argue that the intentional appearance of instability and the implied triumph over this difficulty function as visual pronouncements of the sculptor's technical ingenuity as well as the patron's magnificence. The critical role of primary sources in historical interpretation, evidenced in Marder and d'Amelio, is characteristic of several essays in this volume. Andrea G. De Marchi's contribution turns our attention to the Pamphilj's art collection and the family's first collector, Camillo. In his focused study of Guercino's Endymion, which includes the notable depiction of a telescope, De Marchi brings together two interests of collectors: paintings and scientific instruments. He argues that the telescope was added to the painting at a later moment under the auspices of Camillo. The painted version matches an actual telescope probably made by Galileo and recorded in Camillo's inventory. Catherine Puglisi considers another aspect of the family's art collection, that is, the role of the collection inherited by Olimpia Aldobrandini. Around the turn of the seventeenth century, Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini commissioned Annibale Carracci to paint six lunettes for the vault of his private chapel, which were mostly executed by Carracci's students, especially Francesco Albani. Puglisi examines the original context of the lunette paintings, the unusual choice of media in the chapel-oil on canvas for the vault lunettes over wall paintings in fresco-and the change in function that resulted when the paintings were subsumed into the gallery of the Palazzo Pamphilj al Corso.

Laura Stagno's essay on the patronage occasioned by the marriage of Anna Pamphilj, sister of Benedetto, and Giovanni Andrea III Doria Landi moves the study forward to the next generation. Stagno examines the use of the visual arts, in various media, in the calculated negotiations and subsequent celebration of the marriage and introduces the integral role of music in the family's patronage activities. With the aim of reviving the ephemeral arts associated with the Pamphilj, the cantata written for this wedding, Alessandro Stradella's L'Avviso al Tebro giunto, was performed by the Boston Early Music Festival (BEMF) at the conference held at Boston College. It was the premier performance of the cantata in the United States. The lyrics of the cantata and their translation into English, from the critical edition recently prepared by the Edizione Nazionale dell'Opera Omnia di Alessandro Stradella, are reproduced herein and accompanied by an introduction written by Carolyn Gianturco and Eleanor F. McCrickard.

The remaining essays focus on Benedetto Pamphilj, together functioning as a collective biography. The first section takes up his formation and career with the aim of understanding our subject as a whole person rather than only in his role as patron. The historian Paul F. Grendler explores what subjects Pamphilj studied at the Collegio Romano, who his teachers were, how far he advanced, and what it meant to be educated at the Jesuit College in Rome. James Weiss picks up where Grendler leaves off, following Cardinal Pamphilj's ecclesiastical career in careful detail. By placing his career within the context of the Sacred College, Weiss offers an astute assessment of his role in contemporary society, religion, and politics. And he delves further, offering a character analysis of Pamphilj based on contemporary sources.

The next section of the book focuses on Cardinal Pamphilj's patronage of the visual arts. In my essay on his art collection and especially his still-life paintings, I utilize the payment records to define with greater precision the chronology, character, cost, and significance of his collecting habits. Daria Borghese also relies on the payment records to reconstruct the cardinal's sponsorship of the ephemeral arts of banqueting and other entertainments, concluding that these activities were continuously present in the cardinal's life and served to demonstrate his princely virtues. Stefanie Walker's study focuses on one grand possession of Benedetto Pamphilj, the elaborate Sunflower Carriage designed by Giovanni Paolo Schor. In reconstructing this now-lost object and the economics of its production, Walker demonstrates that the great expense of the carriage matched its significance, for it communicated the status of its owner, as he emerged as an independent young man in Roman society.

The section on the musical interests of Cardinal Pamphilj presents one essay on the role of a famous composer in the patron's entourage and another on a little-known musician in his employ. Together, the contributions furnish a picture of the workings of his musical court. Ellen Harris, who has played a major role as the music consultant for this project, develops her work on the relationship between George Frideric Handel and Cardinal Pamphilj by shifting her perspective from the composer/musician to the patron. She analyzes the theme of resurrection in Pamphilj's lyrics, which Handel set to music, and what this imagery might suggest about the relationship between these men. Alexandra Nigito discusses Cardinal Pamphilj's weekly accademie musicali (later called conversazioni), which were an institution in the Roman court, and introduces the instrumental role of Carlo Francesco Cesarini in these events over the course of four decades.

In the final section of the book, three scholars explore the written word and Cardinal Pamphilj's involvement as creator, collector, and protector in the world of literati. Laurie Shepard studies a theme that moves us beyond the specific interests of Cardinal Pamphilj to the broader literary phenomenon of the pasquinade and its role in the discourse of power and dissension in Baroque Rome. The contributions of Alessandra Mercantini and Vernon Hyde Minor return us to the cultural activities of Pamphilj. By analyzing a previously unknown inventory as well as payment documents, Mercantini accomplishes the monumental task of reconstructing the cardinal's two libraries and their later dispersion. In addition, she considers what the books tell us about Pamphilj's intellectual interests and identity as an erudito. Minor's contribution places Benedetto Pamphilj within the context of the Arcadian Academy, considering what his long-term membership in this literary society and his poetry written in the pastoral mode of Arcadia might suggest about his character, literary interests, and life.

Cardinal Benedetto Pamphilj, Conspicuous Consumption, and the Late Baroque

What do these studies tell us about Cardinal Pamphilj's contribution to the society and culture of Rome in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century? This is a complex question, not the least because this period, sometimes called the late Baroque, remains a relatively murky and ill-defined moment in the history of Rome. Bernini was dead, and Antonio Canova not yet born. The late Baroque is on the cusp of the age of the Grand Tour, when Rome was to enjoy primacy as the cultural referent of Europe and well-bred Northern Europeans, especially the British, were to flock to the city as a rite of passage to cultural enlightenment.7 In Rome, these young men, and sometimes women, experienced the ancient roots of civilization through the city's material remains and studied first-hand the artistic treasures of her more recent past. Paula Findlen argues that it was not only antiquities, but also music, that lured Grand Tourists to Italy: In The Present State of Music in France and Italy (1771), Charles Burney "…[presented] Italy as a feast for the ears as well as the eyes."8 Although foreigners had visited Rome during Pamphilj's lifetime-as they had for centuries-the cultural pilgrimage to the heart of Western civilization had not yet grown into a ritualistic and recognized phenomenon. Heather Hyde Minor has recently identified Clement XII's pontificate (1730-1740) as the start of a major reform of Italian culture, which was promoted by the papacy and spearheaded by "a loosely knit group of intellectuals."9 This cultural reform dovetailed with the flowering of the Grand Tour. Cardinal Pamphilj's life ended, quite literally, at the moment when this period of enlightenment began; he died during the conclave that elected Clement XII. Furthermore, in the canon of art history, the art of late Baroque Rome, also called the barocchetto, has traditionally been characterized as degenerative in comparison to its sixteenth- and seventeenth-century ancestors and to contemporary developments elsewhere in Italy and Europe, and the city as a political and religious entity has been perceived as suffering from a similar state of decline.10 Only recently have scholars begun to revise this narrative of late-seventeenth and eighteenth-century Italy, beginning with the monumental exhibition in the year 2000, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art: Art in Rome in the Eighteenth Century.11

Our study of Cardinal Pamphilj contributes to illuminating the period between the Baroque and the age of the Grand Tour. As Christopher Johns argues, the problem of defining this period arises, in part, from the traditional art historical methodology of classifying and judging art according to formal qualities rather than historical circumstances. In other words, the barocchetto does not fit into the sweeping narrative of art history as it has been written. To his point, I would add that if we look at the period from the perspective of the consumption of the arts-and Cardinal Pamphilj's microhistory is a starting point for this approach-then the late Baroque appears to have been an active period of artistic production. Moreover, I would argue that through his patronage and consumption of the arts, in their broadest possible definition, Cardinal Pamphilj contributed to shaping the culture of the city that was soon to attract Grand Tourists. He was involved in all of the institutions-in some cases, in their early stages-that came to characterize Enlightenment Rome: princely collections, academies, libraries, and conversazioni.12 His patronage of the arts was directly related to his embodiment of taste, and this ability to discern was what some travelers sought to acquire.13 Indeed, Cardinal Pamphilj sustained and promoted the very things that made Rome the requisite experience, a sentiment summed up by Samuel Johnson in 1776: "A man who has not been to Italy is always conscious of an inferiority from his not having seen what is expected a man should see."14

In the past decade scholars of early modern Italian painting have been investigating the relationship between art and economics, an inquiry that has proved illuminating for their counterparts who study Northern European art. The approach has produced new ideas about how paintings were made and sold, the economic status of painters, the consumers of pictures, the role of the art market in collecting, the economic value of art, and more.15 This interest in the economics of painting is connected to a second theme, conspicuous consumption, which has garnered attention in Italian Baroque studies since the historian Peter Burke's seminal essay of 1987, "Conspicuous consumption in seventeenth-century Italy."16 The act of consuming and displaying artistic commodities communicated qualities about the consumer: identity, social status, and wealth. The social historian Renata Ago has recently studied the function of possessions in Roman society. Building upon Kryzstztof Pomian's influential Collectors and Curiosities, Ago discusses the metamorphosis of material goods from items of economic worth into objects of sacred value, or from things into signs.17 She concludes that the two are inextricable. Furthermore, the material goods "speak about their owner in a public, exterior, and socially recognizable manner."18 To be sure, this function is operative in all aspects of Cardinal Pamphilj's patronage and collecting, from the paintings that hung on his walls to the rich banquets he hosted, his Sunflower Carriage, the operas and concerts he sponsored, the books that filled his library, and all of his luxury objects. These consumables, even when ephemeral, communicated something putative about his pedigree, his position in the world, his taste, and even his character.

Cardinal Pamphilj's consumption activities are conducive to socio-economic scrutiny for two reasons: he was an active participant in the market for paintings in Rome, and a plethora of documentation for his consumption exists in the Archivio Doria Pamphilj.19 Several contributors have used these financial records to determine how much the cardinal spent on luxury goods, objects he collected, and ordinary things. By comparing the costs of the items, we can begin to understand relative economic value. I have calculated that Pamphilj spent about 1,138 scudi on paintings during his first period of collecting (1673-1684) and a bit over 2,000 scudi during his second period (1708-1720). Many individual paintings cost only a few scudi, but they occasionally cost more, 10, 20, or even 50 scudi. Pamphilj's expenditure on paintings is small in comparison with what he paid for a single carriage, albeit an especially ornate one. Walker demonstrates that for his Sunflower Carriage, which he commissioned from Giovanni Paolo Schor in 1673, the work of the bronze caster (ottonaro) alone was billed at over 2,500 scudi although counter estimates reduce this figure to between 987 and 1,750 scudi. Nevertheless, the bronze casting was only one part of its production; bills arrived from the carriage builder, saddler, upholsterer, metalworker, and gilder, not to mention Schor's presumed payment for the design. And as Walker notes, this is not the only carriage owned by Benedetto Pamphilj. Although a systematic survey has not been done, his accounts of 1680 record a calash, a light, small-wheeled vehicle with a folding top.20 From 1672 to 1711 there are frequent payments for work carried out on carriages in Pamphilj's Registri di mandati, totaling 5,661.48 scudi (which do not, however, include the payments for the Sunflower Carriage).21 The expense of a carefully designed and crafted carriage-an object in the category of the decorative arts today-greatly exceeded the economic value of most paintings, especially the minor genres, which was Pamphilj's preferred subject matter. As Walker argues, carriages played a major role in the ritual of display and social exchange. Riding in one's carriage was a more public means of communicating identity than an art collection displayed inside a princely residence. With paintings being comparatively cheaper, an exquisite carriage might have held more weight in the competitive world of conspicuous consumption. To be sure, both the art collection and the carriage were necessary trappings of the aristocracy.

In interpreting the economic and symbolic value of possessions, it is interesting to note that our modern hierarchy of the arts as encapsulated in the institution of the museum inverts their relative worth. Paintings-treated as isolated individual objects of great cultural value-have traditionally been privileged over the decorative arts that are displayed in more crowded and often lesser spaces in fine art museums. An alternative practice is to divorce the two categories, once displayed together in palaces, in two separate types of museums. The practice of division, however, is beginning to change. In 2006, the exhibition, At Home in Renaissance Italy, at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London integrated the paintings and objects with the aim of conjuring the spaces they originally occupied. At the new Art of the Americas wing at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the concept of integration has been applied to a permanent installation. The public practices of the museum reflect the shifts in academia, where the relatively recent study of material culture has served to broaden the scholarship and the curriculum of art history. This study of Benedetto Pamphilj further proves the point for early modern Italy: The so-called decorative arts held as much, if not more, economic and symbolic value than pictures, despite the elevation of painting to the status of the liberal arts in the sixteenth century.

The study of collecting in early modern Italy has recently been pushed in an exciting and new direction by asking not merely what was collected but how material culture was displayed. At the forefront of this effort is the Getty Research Institute's major project, "Display of Art in Roman Palaces, 1550-1750," directed by Associate Director Gail Feigenbaum. The research team is studying how paintings, sculptures, drawings, textiles, and other objects were integrated into their original environment and how their display-a word that has no equivalent in early modern Italian-was a dynamic process, a continual performance, embodied in contemporary Italian by the word, dispiegato, unfolded or unfurled.22 The focus on display and on the integration of different types of objects provides a model for the future study of the possessions of Cardinal Pamphilj as well as other members of the family within the environment of the Palazzo Pamphilj al Corso.23

Comparisons between Cardinal Pamphilj's cultural activities and their costs reinforce the notion that paintings as a category of material goods did not hold a privileged place at the top of the hierarchy of consumption. Borghese argues that Pamphilj not only spent a lot on banqueting, luxury objects associated with entertaining, and specialty foods to serve his guests, but that such ephemeral entertainments were a constant presence in his life. The succession of banquets, refreshments, comedies, operas, and concerts was a continual and dynamic instrument of self-fashioning. Besides recording the cost of Pamphilj's consumption habits, the account books reveal his patterns of behavior and thus allow us to infer which activities most engaged him and his bank account. Book collecting, another sign of prestige,24 is certainly one of them, for Mercantini's essay demonstrates that our patron was continuously engaged in acquiring books. Nigito likewise argues that music was a constant recipient of Pamphilj's patronage and attention. If we were to look only at the number of pictures (1,400) owned by Pamphilj near his death, we might conclude that he was most passionate about art collecting. The chronology of his behavior, however, suggests a different interpretation. His art collecting was confined to two periods that coincide with specific events in his life, which likely prompted his behavior. When one compares the amount of time and money he spent on collecting paintings versus books, music, or banqueting, the former accrues less significance. Nevertheless, his art collection was one element of prestige among many. We might think of the paintings as the backdrop, or the scenery, for other displays of magnificence. In providing a comprehensive perspective on Pamphilj's consumption habits, the account books allow us to interpret the relative importance of the things he bought and the cultural endeavors he sponsored. Viewed as a whole, his expenditures reveal a patron actively engaged in the consumption of both material goods and ephemeral activities that contributed to creating the image of a magnificent nobleman.

Just how magnificent Benedetto Pamphilj was is difficult to determine. As Borghese concludes, his activities were part of an accepted practice that had begun in the Renaissance and flourished in the Baroque, with patrons and collectors like Marquis Vincenzo Giustiniani, Cardinal Francesco Maria Del Monte, Cardinal Scipione Borghese, Cardinal Francesco Barberini, Marcello and Giulio Sacchetti, Cardinal Bernardino Spada, Camillo Massimo, and Benedetto's own father, Camillo Pamphilj.25 Using Giustiniani and Del Monte as examples, Ago makes the point that collectors identified with their collections.26 Like Benedetto Pamphilj, many of the collectors in this list are cardinals; these men formed a particular patronage group in the papal city that used material culture to define their identities.27 I argue that Cardinal Flavio Chigi might have offered a specific precedent for Pamphilj's formation of a collection privileging still-life paintings. Although still-life paintings had been on the Roman market since at least 1600, in mid-century they still represented a small percentage of most noble collections; thus, Chigi's collection stands out as a forerunner. Borghese, Harris, and I all suggest the possibility that Cardinal Pamphilj in turn might have provided a model-in his dual interests of music and collecting and in some of the specific musicians and artists he hired-for his younger peers, Cardinal Pietro Ottoboni and Prince Francesco Maria Ruspoli. Harris argues that Ottoboni and Ruspoli upstaged their model when Handel gravitated to their circles and commentators in the 1710s overlooked Pamphilj's musical patronage but muses that the older Pamphilj might not have minded taking a back seat to his younger protégés. Despite Pamphilj's conformity to an existing patronage model, the combination of his choices resulted in a unique identity, something that is true of course for all patrons.

A Collective Biography of Cardinal Benedetto Pamphilj

What began as a patronage study has evolved into something more, a collective biography. Several essays move beyond the issues of patronage, collecting, and consumption to consider other aspects of Benedetto Pamphilj: his character, the events in his life, his interests and passions, and even his ideas about love. As is often true of biography, the portrait that has emerged is complex and even contradictory. At one moment Pamphilj appears determined and focused, at another diffident and apathetic. He is at once central to the papal court, yet absent from its significant events; ever present, yet insignificant; connected to the key figures of his day, yet somewhat peripheral. Despite the inconsistencies, or perhaps because of them, the authors' varied approaches and conclusions offer deep insights into Pamphilj as a human being.

Two papers in particular present a contradiction of character. In analyzing the young Pamphilj's education at the Jesuit Collegio Romano, Paul Grendler suggests that he was a man of exceptional preparation and notable intelligence. While acknowledging that Pamphilj's pedigree might have counted in his favor, Grendler makes the point that few students advanced to the level that Pamphilj did. In 1673, Pamphilj joined the ranks of the best students by presenting a formal disputation of "all of Philosophy;" and in 1676 he was allowed to perform the "General Acts," which was a rigorous disputation concerning theology. Two weeks later he received a doctorate of philosophy and theology. Such academic success suggests a hardworking, intelligent, and perhaps ambitious individual, someone who intended to make his mark in his destined career in the Church. James Weiss's essay takes up where Grendler ends, but what he finds is unexpected: Pamphilj's youthful promise seems to have gone unfulfilled. Pamphilj did indeed become a cardinal, in 1681, thanks to the system of "paying back the hat."28 His great-uncle Innocent X had created Benedetto Odescalchi a cardinal; now it was the turn of Odescalchi as Pope Innocent XI to raise his benefactor's relative to the Sacred College. With a more critical eye than Montalto, Weiss examines Pamphilj's posts in the Curia in the context of the major religious and political issues and events that occurred during Pamphilj's forty-nine years as a cardinal. He concludes that Pamphilj did not hold decisive positions, instead performing honorific ones, and "stood apart from every major political or religious question facing the papacy."29 Nevertheless, Weiss does argue that he was effective in some positions: papal legate in Bologna, cardinal protector of the papal port of Civitavecchia, and archpriest of Saint John Lateran. It seems that much of his energies were spent on cultural pursuits. In focusing on patronage, Cardinal Pamphilj was fulfilling the unofficial duty of his office of creating a magnificent satellite court that burnished the reputation of the papacy and, in his patronage activities at Saint John Lateran, he was fulfilling the role of a cardinal as a benefactor of the Church.30 Although the seeming disconnect between his formation and career cannot be fully reconciled, both authors proffer insights into our subject and contribute to our picture of Pamphilj as a multifaceted individual.

Several authors probe Benedetto Pamphilj's character from differing perspectives and sources, but all reach a similar conclusion: He was a man of deeply felt sentiments. Weiss analyzes the major contemporary source-Count Orazio d'Elci's description of Cardinal Pamphilj in his Relatione della Corte di Roma (1699)-as well as other notices that offer glimpses into his character. He evokes a magnanimous cardinal and a man who is sensitive, melancholic, diffident, and even indolent while endearingly vivacious and cheeky. He points to one particular moment in d'Elci as the source of the cardinal's profound feelings: the death of his mother. After she passed away in 1681, Pamphilj underwent a change in character, from a vivacious young man who participated in public entertainments and pursued love, to someone plagued by melancholy, someone who had removed himself from earthly delights and devoted himself entirely to spiritual concerns. I would argue that the timing is notable. The year of his mother's death is the same one in which he became a cardinal. Might this reported change in character have had something to do with a new sense of adulthood and probity that coincided with his mother's death and his new position in Roman society?

D'Elci asserts that the cardinal is "living at present in great Devotion."31 Although he was referring to the cardinal's change in lifestyle in 1681, he wrote this in 1699. Are we to believe that Pamphilj continued to eschew "all his Divertisements" nearly two decades after his mother's death?32 How are we to reconcile this reclusive and abstemious character with what we know of his patronage of the arts? The essays on his musical patronage furnish evidence that puts into question d'Elci's assertion. Harris acknowledges that the lyrics of Hendel, non può mia musa seem to imply that "…the composer had brought his [Pamphilj's] muse back to life after it had fallen silent" but nevertheless concludes: "Although it may be, as d'Elci states, that Pamphilj had given up public diversions, he continued writing oratorios and cantatas without any discernible hiatus before 1707. That is, his poetic imagination, based on the texts that survive, did not need reawakening."33 Nigito, in her essay on Carlo Francesco Cesarini and Pamphilj's conversazioni, reinforces the point; music was a constant presence in the cardinal's life, and Cesarini played a major part in it for four decades. The collective evidence and interpretations of Pamphilj's life suggest that we cannot read d'Elci's statements without a critical eye. Furthermore, a broader historical perspective may offer some context for the apparent contradictions and a possible avenue for further study of Pamphilj's character and patronage. In analyzing the Camerino in Palazzo Farnese, with Annibale Carracci's The Choice of Hercules (ca. 1596) and other Herculean scenes, Ophur Mansour has recently illuminated the delicate balance between the "persons" of the cardinal in post-Tridentine Rome, at once secular prince and apostolic successor.34 By analyzing the Hercules paintings commissioned by Cardinal Odoardo Farnese within the context of three texts about the role of cardinals, he argues that cardinals, in particular ones from noble houses, had to mediate between the seemingly conflicting roles of nobility and wealth, on the one hand, and piety and poverty, on the other. Yet, Mansour concludes that these roles shared the common goal of attaining personal virtue and essentially "…were compatible and mutually reinforcing."35 At the opposite end of the century, it seems that Cardinal Benedetto Pamphilj still embodied such apparent contradictions of character, thought, and action, but if we listen to his poetry, he too emerged virtuous.

What better ending than a foray into love? The contemporary D'Elci implies that as a youth Benedetto did pursue love, but what this means-what he thought about love-is open to speculation. A few of the contributors bravely take up the issue. Raising the point, Weiss notes the rumors of Pamphilj's love intrigues with young ladies as well as his camaraderie with "a coterie of prelates and aristocrats where same-sex attractions were acknowledged in coded fashion."36 Harris has illuminated the issue in her groundbreaking work on Handel's relationship with Pamphilj; in the present study, she revisits the theme in the specific imagery of rebirth in Pamphilj's text for Hendel, non può mia musa, as well as in his other lyrics, all of which were set by Handel. Arguing that Pamphilj's pastoral texts are reflections of their author (as was often true in the characteristically ambiguous pastoral), Harris probes their imagery to conjure in a most subtle way the synergetic relationship between Pamphilj and Handel. The composer and his beautiful music are at once an inspiration and a temptation, yet the patron ultimately retains his probity and his composure. In expressing the presentation of a choice, the exercise of judgment, and the ultimate selection of rectitude, the lyrics written by Pamphilj function in a similarly self-reflective manner as Cardinal Farnese's Hercules paintings in his Camerino, returning us to the complex nature of the cardinal. What differentiates the respective cases of Pamphilj and Farnese is that the former was also the author. It seems that only a man possessing great depth and range of emotion could have written such subtly evocative lyrics, ones that Handel matched with equally suggestive music.

Vernon Hyde Minor teases out aspects of Pamphilj's character by considering what his membership in the Arcadian Academy might suggest about him, describing him as "...a generous, judicious, measured, congenial, and-if we are to believe his own verse-tender and sometimes melancholic poet, patron of the arts, and Arcadian shepherd."37 In this milieu Pamphilj not only wrote about the pastoral, but he embodied it by assuming the identity of a shepherd. Minor describes, through the conduit of poststructuralist language, the Arcadian Academy as a site of discourse: "All that means is both concretely the Arcadian Academy and somewhat more abstractly the idea of Arcadia can be seen as nodal points in a complex web of relationships and interconnections in terms of ideas, history, and society, along with literary, musical, and artistic traditions, and-most significantly for such a theorist as Michel Foucault-power."38 And like Harris, Minor interprets the pastoral mode as imbued with multiple and even competing meanings, which reflect the reality of eighteenth-century Rome while simultaneously masking it. According to the tradition originating in Antiquity, one element in this complex web is the acceptability of same-sex attractions; Arcadia is a place of love and innocence and, as such, it is free from judgment. In conjuring this site of discourse, and introducing Pamphilj's poetry into it, Minor evokes notions of Pamphilj's desires and associations with love while avoiding declarative interpretations.

Minor's identification of the Arcadian Academy as a site of cultural reform opens further avenues for inquiry into the role of Benedetto Pamphilj in late Baroque culture. Elisabetta Graziosi, in Italy's Eighteenth Century, also presents the Arcadian Academy as a progressive institution.39 She argues that the Arcadians challenged gender norms by admitting women on a regular basis, which in turn stimulated the publication of poetry by female authors in the early years of the eighteenth century. As the first academy to take the "modernizing leap" of admitting female members,40 it set off "a domino effect in other academies and other editorial enterprises."41 What did Benedetto Pamphilj think about the reform of culture and about the place of women in society? Was he merely a witness to these reformist ideas, or a supporter? Pamphilj was also associated with a second enlightened enterprise in Rome, the world of scientific inquiry. Although De Marchi rejects an interpretation of Guercino's Endymion as proof of the Pamphilj family's support for scientific advances, noting in particular Innocent X's aversion to such ideas, there is enough evidence to connect the papal nephews (if not the pope) to scientific inquiry (their level of engagement, however, remains to be determined). Camillo, Giovanni Battista, and Benedetto all owned telescopes, as De Marchi notes, and Mercantini shows that Benedetto also acquired scientific books and was associated with Giovanni Giustino Ciampini, the founder of a scientific academy in Rome. Although it would be premature to interpret the significance of Benedetto Pamphilj's association with these progressive elements in society, the issue merits further investigation. But, first, there is much to learn about Cardinal Benedetto Pamphilj and late Baroque Rome in the pages of this book.

1 For a virtual visit to the Galleria Doria Pamphilj, see its Web site: www.dopart.it/roma/.

2 This synopsis relies on Lina Montalto, Un mecenate in Roma barocca. Il cardinale Benedetto Pamphilj (1653-1730) (Florence: Sansoni, 1955). For more on Montalto, see below.

3 Francesca Cappelletti, "Palazzo e collezione fra Sei e Settecento. Il Principe Giovanni Battista e il cardinale Benedetto Pamphilj," in Il Palazzo Doria Pamphilj al Corso e le sue collezioni, ed. Andrea G. De Marchi, 1st ed. (Florence: Centro Di, 1999), 70.

4 See note 2.

5 I owe this idea to Andrea G. De Marchi. Francis Haskell, Patrons and Painters. A Study in the Relations Between Italian Art and Society in the Age of the Baroque (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1963).

6 Marder and d'Amelio, 27.

7 Christopher M.S. Johns, "Entrepôt of Europe: Rome in the Eighteenth Century," in Art in Rome in the Eighteenth Century, ed. C.M.S. Johns (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2000), 17-45.

8 Paula Findlen, "Introduction: Culture and Gender in Eighteenth-Century Italy," in Italy's Eighteenth Century. Gender and Culture in the Age of the Grand Tour, ed. Paula Findlen, Wendy Wassyng Roworth, and Catherine M. Sama (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009), 3.

9 Heather Hyde Minor, The Culture of Architecture in Enlightenment Rome (University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2010), 3.

10 Johns, 17-20.

11 The catalogue is edited by Christopher M.S. Johns; see note 7. Other recent studies on the period include Vernon Hyde Minor, The Death of the Baroque and the Rhetoric of Good Taste (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006); and Minor, The Culture of Architecture. For an interdisciplinary perspective, Paula Findlen, Wendy Wassyng Roworth, and Catherine M. Sama, eds., Italy's Eighteenth Century. Gender and Culture in the Age of the Grand Tour (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009).

12 Minor, The Culture of Architecture, 7-12, outlines the cultural and intellectual structures fundamental to Enlightenment Rome.

13 Findlen, 2.

14 Qtd. in Findlen, 2.

15 Some examples include Marcello Fantoni, L.C. Matthew, and S.F. Matthews-Grieco, eds., The Art Market in Italy, 15th-17th Centuries (Ferrara: Franco Cosimo Panini, 2003); Francesca Cappelletti and Silva Danesi Squarzina, eds., Decorazione e collezionismo a Roma nel Seicento, (Rome: Gangemi, 2003); Patrizia Cavazzini, Painting as Business in Early Seventeenth-century Rome (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2008); Jonathan K. Nelson and Richard J. Zeckhauser, eds., The Patron's Payoff: Conspicuous Commissions in Italian Renaissance Art (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008); Richard E. Spear and Philip Sohm, Painting for Profit (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010).

16 Peter Burke, The Historical Anthropology of Early Modern Italy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 132-49. By now the concept of conspicuous consumption permeates early modern patronage and collecting studies.

17 Renato Ago, "Collezioni di quadri e collezioni di libri a Roma tra XVI e XVIII secolo," Quaderni storici XXXVII.2 (2002); Ago, Il gusto delle cose. Una storia degli oggetti nella Roma del Seicento (Rome: Donzelli, 2006).

18 Ago, Il gusto delle cose, XVIII.

19 The two principal types of documents that record Pamphilj's expenditures are the Registri di mandati and the Filze dei conti e delle giustificazione; for a full explanation, see my essay, 114.

20 ADP Sc. 1.43, fol. 195, March 30, 1680: Stefano Zanetti is paid 25 scudi for "una cassa di calesse."

21 ADP Sc. 1.42 (1672)-Sc. 1.47 (1711), passim.

22 The publication from this research project is scheduled for 2012. My description of the project is based on notes taken during Gail Feigenbaum's introduction to the conference of the same title, held at the Getty Research Institute, December 2011.

23 There has already been some work done on the display of paintings in the Galleria Doria Pamphilj; see Andrea G. De Marchi, ed., Il Palazzo Doria Pamphilj al Corso e le sue collezioni, 2nd ed. (Florence: Centro Di, 2008). I am currently developing this work further in a study of the display of art in the Pamphilj palaces in Rome before the arrival of the Doria in the late eighteenth century.

24 Ago, "Collezioni di quadri," 381.

25 Haskell remains a fundamental source on Roman collections although the bibliography on individual patrons and collectors has grown exponentially over the past half century. For some additional sources, see my essay in this volume.

26 Ago, Il gusto delle cose, 22.

27 A recent volume on how cardinals used patronage to articulate and communicate identity provides an excellent summary of the role of cardinals (see the "Introduction") and an informative series of case studies: Mary Hollingsworth and Carol M. Richardson, eds., The Possessions of Cardinals. Politics, Piety, and Art, 1450-1700 (University Park, Penn.: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2010).

28 Weiss, 98.

29 Weiss, 98.

30 Gigliola Fragnito, "Cardinals' Courts in Sixteenth-century Rome," Journal of Modern History 65 (1993): 38-39.

31 Qtd. in Weiss, 102.

32 Ibid.

33 Harris, 193.

34 Ophur Mansour, "Cardinal Virtues: Odoardo Farnese in his Camerino," in The Possessions of Cardinals. Politics, Piety, and Art, 1450-1700, eds. Mary Hollingsworth and Carol M. Richardson (University Park, Penn.: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2010), 226-48.

35 Mansour, 238.

36 Weiss, 98.

37 Minor, 303.

38 Minor, 304.

39Elisabetta Graziosi, "Revisiting Arcadia: Women and Academies in Eighteenth-Century Italy," in Italy's Eighteenth Century. Gender and Culture in the Age of the Grand Tour, eds. Paula Findlen, Wendy Wassyng Roworth, and Catherine M. Sama (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2009), 103-124.

40 Ibid., 107. For further discussion of the role of women in eighteenth-century Italy, see Findlen above.

41 Ibid., 114.