Introduction

Valuable manuscripts containing descriptions and maps of Sicily are kept today in different national and international libraries, concerning a wide chronology. These military and cartographic documents are an important source for the study of the defensive strategy of the Spanish Empire in the Mediterranean during the 16th and 17th centuries. Some of these texts, such as the Descripción de las marinas de todo el Reino de Sicilia (1596), [1] the Descrittione del Regno de Sicilia (1677) [2] and the Teatro geográfico antiguo y moderno del Reyno de Sicilia (1686) [3] have been the subject of studies over the past decades by researchers such as Alicia Cámara, Marco Nobile and Valeria Manfrè.

Nevertheless, there is still a wide range of unpublished documents of great interest on this subject. [4] Some of the most representative examples are: Sicilia insulam descriptio, Sicilia insulam descriptio, attributed to the friar Simone da Lentini (12th century) [5]; the Descrittione della fellicisima città di Palermo, by the gentilhombre Gaspare di Reggio from Palermo (1599) [6]; and the Descripcion del Reino de Sicilia, by the philosopher Bernabé de Cepeda (1735) [7]. All these texts offer, to different extents, relevant information on the strategic planning of the defense, on the military architecture and on the governing of the main Sicilian cities during the medieval, modern and contemporary periods.

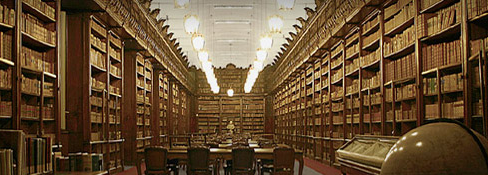

One of these texts, the Descrittione della fellicisima città di Palermo (1599), by Gaspare Di Reggio, stands out above the rest. It is a manuscript that contains military information, today kept in the Biblioteca General de Palacio in Madrid. So far, there is no previous studies focusing on this manuscript and often it has been relegated to a secondary level despite the interesting context in which it was elaborated and the quality of its content. This is why the main goal of this article is to provide a first approach to the manuscript, which will allow me a deeper study in the future. Only by considering the contribution of Gaspare di Reggio and looking further into these unpublished descriptions of Sicily, we will be able to get a better knowledge of the island. It will also be necessary to establish a comparison of this kind of texts with others written in other territories such as Naples and Milan. Only then we will be able to reaffirm the hypothesis that these were a popular narrative genre in the Sicilian and southern Italian context and they shared common points with the chorographic and descriptive manuscripts from other territories in the Italian Peninsula. [8] I also intend to show that the municipal governing institutions and the local ones from Sicily used literary persuasion to obtain support for their proposals.

The Descrittione della felicissima città di Palermo

It is a manuscript that must be considered along with the scarce yet extraordinary genre constituted by the accounts and descriptions of Sicily in the Early Modern Age [9]. Regarding its form, it is composed by an extensive text of 60 pages with double pagination, a frontispiece [10], and no visual or cartographic images. It was written using the ductus fermo writing, with a simple language and rare mentions to the classical Sicilian past history. Regarding its structure, the text presents alphabetical and content indexes and a brief introduction. It is followed by two parts: the first one dedicated to the urban and defensive morphology; and the second one to the description of Palermo's political institutions. This is a relatively common model for this sort of works, especially if we compare to others presenting similar characteristics which were offered to the viceroy, such as the one from Antonio de Bolonia to the duke of Osuna in 1610. [11]

Among the rich documentation on the government of Sicily in the Archivio di Stato di Palermo [12] and in the Archivo General de Simancas [13], there are neither allusions to the manuscript of Di Reggio nor any notes to its commission. We also do not have any references mentioning its delivery to the duke of Maqueda in 1599 or to attest the possibility of being sent to the court in Madrid. In order to understand the lack of references in the sources, we must refer to another description of Sicily, from the first half of the 17th century. It is the work of Carlo Maria Ventimiglia and Francesco Negro, Atlante di città e fortezze del regno di Sicilia (1634-39) [14]. This work caused great fear in the Consejo de Italia, as it contained highly valuable military information that should have remained known only to the viceroy, his men of trust and the council itself. Having this in mind, it might be possible that Di Reggio's description was known only by a restrict number of men in order to avoid its information to be diffused. It would have been especially dangerous if it reached the Turkish spies living in the coast.

The autor: Gaspare di Reggio

As it was mentioned earlier, the Descrittione was elaborated by Gaspare di Reggio, a gentilhombre from the Palermo's elite. He had a vast knowledge of military engineering and cartography, despite being a jurist. At the time he wrote the text, he was one of the razionali of the Tribunale del Real Patrimonio which meant he was in direct control of the finances of the kingdom. We also know that before this text, he wrote eight years earlier, Sommario delle historie del regno di Sicilia che seguono quelle del padre fra Tomaso Facello ove si vede quanto di notabile e nell'istesso regno accaduto dell'anno 1546 in sino a quello del 1593. [15] In this work, he used the manuscripts of the well-known Dominican friar to narrate the main historical moments of the reign during the second half of the 16th century. [16] We have very little information about his posterior career as a writer. [17] However, the same does not happen concerning his administrative work. We can trace Di Reggio's activity in the documents (letters and memorials) of the Tribunale del Real Patrimonio during the first half of the 16th century.

The urban and defensive context in 16th century Palermo

Authors such as Domenico Ligresti [18] and more recently, Valentina Favarò [19] and María del Pilar Mesa [20], pointed out that Sicily played an essential role as a barrier against the Turkish attacks to the Italian reigns. A situation that would slowly change as the Hispanic military conflicts moved to the interior of Europe. Despite this change, when analyzing the instructions given by the kings to the viceroys appointed in Sicily during the 17th century, the issues concerning the defense had still a primary weight in their government. In the mid-17th century, Sicily had become once again a laboratory for rehearsing the most modern defensive solutions.

Nevertheless, beyond all the official orders and the reports of the leaving viceroys, the new alter ego arriving to Palermo did not have anything else to guide him in his political and military decisions. This might be the reason why cartographers and military engineers made different descriptions at the urge of the local institutions, such as the senate and the cities' local governments. Their goal was to share with the viceroy the state of the defensive constructions in places affected by Turkish attacks and the means to combat them.

Di Reggio was in a good position to realize how important defense was to the king and to the viceroy, thanks to his experience in economical and governmental affairs. He did not hesitate in leaving to a second place the details related to the development of the island. This was the reason why, through the Descrittione, a text mainly persuasive, the author meant to inform the new viceroy about the interests of the ruling and economical classes of the capital. A city that, in the author's opinion, emanated beauty and modernity thanks to the renovatio urbis process that had began in the second half of the 16th century impelled by political representatives and viceroys as Juan de Vega (1547-1557) and García Álvarez de Toledo (1565). The capital had suffered a deep urban reorganization which converted it in a renovated, functional and accessible city, open to the Italic peninsula and to the Mediterranean.

The maritime activity and the progressive urbanization process of the nobility and the business bourgeoisie had progressively improved the capital of the kingdom in its private and public spheres.

The work of Di Reggio had the obligated need to inform the duke of Maqueda about the strengthening of the military structures, but it was also the vehicle for showing his and the ruling classes' wishes to continue the public works to please the population. Therefore, the Descrittione cannot be considered a neutral text: it intended, sometimes with great intensity, to attract the new viceroy to the interests of the government and economical elite, represented by the senate and the city Comune.

The viceroy duke of Maqueda (1598-1601): the recipient of the manuscript

Don Bernardino de Cárdenas and Portugal, III duke of Maqueda was born to don Bernardino de Cárdenas Velasco, V marquis of Elche and doña Joana of Bragança, daughter of Jaime I, IV duke of Bragança. His paternal grandfather, don Bernardino de Cárdenas Pacheco, II duke of Maqueda, was viceroy of Navarra between 1549 and 1552, and later, viceroy of Valencia during the years 1553-1558. He died in the beginning of 1560, only two years after his son, leaving his grandchild and heir with only seven years-old. His mother was in charge of the administration of his inheritance during his childhood. After serving the wars of religion in France in the decade of 1580, he was appointed viceroy of Catalonia in 1592. During the four years of his viceroyalty in the Principality, he had to face the first stage of the Catalan torbacions. His political action was marked for his strong persecution against the bandits and confronts against the Catalan institutions. After his mandate, he was named viceroy of Sicily, and he arrived on April 1598.

He replaced the count Alba de Liste (1585-1592) and the count of Olivares (1592-1595) [21], who had made considerable efforts in strengthening the walls of Messina, the Nuovo Molo of Palermo and the construction of the new bastions along the northern coast.

Upon his arrival to Palermo, don Bernardino went straight to Messina to organize the army to repel the attacks that every year affected the island during the spring. The Descrittione, most likely, was given to him when he returned to the capital in January 1599.

Contents: the balance between urbanism and defense

The Descrittione we have been presenting in the past paragraphs is a text that combines a detailed description of the defensive structures - men, weapons and fortresses - and the description of the morphology and urban and political anthropology of Palermo. The second half of the text, dedicated to the description of the positions in the government and the limitations of the institutions, has little historical relevance. In its 70 pages, Di Reggio shows a sober style, lacking neutrality. He only refers the existing institutions in the city and their most prominent members: the judge, the members of the Senate and those who belonged to the city government. There is no new information. Instead, it is just a list of titles and posts. As a consequence, we will not focus on this part. The interest of the manuscript is centered in the first part dedicated to the description of the defense and urbanism of the city.

The urban Enterprise

Unlike other similar manuscripts such as the one from Antonio di Bolonia (1610) or the Atlas by Francesco Negro (1634), the work of Di Reggio introduces a novelty: an anthropological analysis of Palermo. Another singularity is the fact that the Descrittione does not start with the list of the defensive elements in the capital to focus on other subjects later. Since a first moment, it is possible to read about the urban and physical reality of Palermo and its inhabitants. Then, the reader can find a description of the organization of the Turkish armies and the defensive elements of the capital. Therefore, the first of the subjects introduced is the description of the public spaces, systems of communication and common areas. The author reveals to the newly arrived viceroy that his vassals wanted him to continue with the "champagne delle publiche strade" [22], in motion since the last decades. When describing the new streets in the city, Di Reggio is following the descriptive model of the "città bella", recently mentioned by Liliane Dufour, who studied descriptive documents from the 16th-18th centuries [23]. In the Descrittione, as it often happens in this kind of manuscripts, there are no references to marginal areas or the outskirts. Instead, the author comments on the beautiful squares and fountains, insisting on the ideal of beauty. Di Reggio comments that the roads are articulated around the "vie di superbisime di palazzi magnifici e di loggie ornate, di delitiose fonate e archi" [24]. He also mentions the old Cassaro, now renamed as Via Toledo, stating that it was promoted by the viceroy who shared the same name, García Álvarez de Toledo (1565-1566), "con superbo artificcio". [25] Then, he focuses on the different noble houses that were now being constructed in the city center, and from here, he starts a description of the privileged groups of Palermo, which he qualifies as the true promoters of this embellishment process. The persistence of Di Reggio of mentioning the urban improvements must be related with the guidelines approved by the city council in 1596, two years before the arrival of the duke to Sicily. The senate had approved the new Strada Nuova that would cross perpendicularly Via Toledo. This new measure established a Latin cross structure in the communication layout, a classical model that divided the city in four equal parts. These would represent a referent to a series of architectonical reforms in each one. The new artery would achieve a key role in the continuity of the economical and commercial development of the city, as it strengthened the mercantile power and had a symbolic meaning for its actors and members of the government who had a majestic new scenario to see and be seen. However, in those days, the government of the island was at the hands of the marquis of Gerace (1595-1598), the interim president of the island, who did not have the means to influence the king Philip III and the Consejo de Italia to allow the works. This explains why the members of the local government sought so desperately the new viceroy's support. He had to understand the project and get involved: only his strong ties with the court in Madrid would authorize the new road.

The Nuovo Molo and the Strada Nuova

After the social and urban analysis of the Sicilian capital, the author starts one of the main parts of his text - the one that refers to the edification of the new port. From page 15 on, he explains the several catastrophes that affected the city as a consequence of the proximity to Argel and the attacks of its fleet. This is one of the most important moments of the Descrittione, considering that Di Reggio not only describes the actual state of the works that are going on in the port, but also advices the viceroy on the best strategies to finish it as soon as possible. More than a mere spectator, the author intervenes in the territory. He reminds the viceroy that García de Toledo (1565) was the one in charge of the magnificent project. However, the economic difficulties the senate of Palermo was going through and the poor state of the coffers of the Tribunale del Real Patrimonio had condemned the project to a slow evolution. This certainly affected merchants and the business elite. The constant need of repair of the walls and the bastions along the coastline - one of the main concerns of the viceroys - had exhausted the tax office. However, the ruling class felt the simultaneous need to continue the port project in order to maintain the trade flow. To solve this problem, Di Reggio attempts to give a solution to the highest authority of the Reign. It is not completely unreasonable considering he occupied a position in the Tribunale del Real Patrimonio. For him, the solution lied in the possibility of taking a part of the tari [26] of the tax on essential goods to finance the new port.

Walls, bastions and the Turks

After the analysis of the urban landscape and the port, the author focuses on the description of the walls and on the military detachment placed for example in Mondelo and in Montagna di Gallo. From that point on, in page 66, he focuses all his attention in the subject that justified the description, the "imprese di barberia". [27] For over 10 pages, Di Reggio informs the duke that the war so far had been defensive and fought mainly in the sea. However, the usual raids in the southern coast of the island eased the way in for the enemies. According to the author, this could be prevented by placing the squadron of galleys in the east coast. He also lists with detail the military contingency of Palermo: canons, armoury, etc, including the number of harquebus and muskets. This recount is still proof of a methodological approach that is historiae vitae magistra, which finishes with the number of horses the capital had available and their location by streets and quartieri. [28] This is especially important as it stresses again the commissioner of this manuscript. The author mentions the constant contribution of the barons, many of whom were members of the Senate, who always offered its economical and material resources to the city in the name of the king.

Final balance

The Descrittione may be considered a true institutional piece of writing. Its main goal was to persuade the new viceroy to continue with the urban renovation and with the Nuovo Molo. As mentioned before, besides the official instructions, the orders given by the Consejo de Italia and the instructions from the resigning viceroy, the new governors did not have a deep understanding of the economical and political details of the island. Under our point of view, the local elite profited from this situation to try to influence the alter ego of the king as soon as he arrived to Palermo. An example of this is the manuscript of Di Reggio: a description of the capital of the kingdom to improve its defence that was in fact a tool of persuasion for the Senate and for the city government.

So, the first part, despite concerning the military reforms, had a clear goal: to explain to the new viceroy, the duke of Maqueda, the urban development of the city. This is why the content goes from the morphologic description of Palermo and the issues related to its defence. The importance of the first subject largely exceeds the one given by Di Reggio to the structures for containing and repelling the foreign attacks. This really reveals his true goals, shared with the ones from the ruling class. All of the aspects mentioned above had to respect the defensive norms of the kingdom along with the ones established by the Monarchy.

We believe that after reading the manuscript, the duke responded very positively to the idea of the urban reforms and to the opening of the Strada Nuova, once the project was presented. He wrote to Philip II to explain the details of the project and the king approved its construction. Some months earlier, the viceroy had received 20.000 ducati from the senate as a form of gratitude for his mediation. This episode makes us believe that in addition to the Descrittione, this sum was the key factor to obtain the support of the viceroy, as well as the compromise to name the Strada Nuova as Via Maqueda, a name that it keeps to the present time.

As a conclusion, we can state that the manuscript of Di Reggio offers not only great novelties in the description of the Sicilian capital, but also a political intention. Hence, the manuscript can be defined as a work that combines geography, the art of war and the ethno-anthropological analysis in an intricate unicum. It witnesses and reflects the complex history of the Sicilian institutions and the private economic interests of its governors.

Bibliography

N. Aricò, Atlante di città e fortezze del Regno di Sicilia, edizione critica di due codici che si conservano presso la Biblioteca Nazionale di di Madrid (Atlante di città e fortezze del regno di Sicilia), Mesina, 1992.

A. Cámara, "Chrorografie et fortification. Spannocchi au service de la monarchie spagnole", in I. Warmoes (coord.), Atlas militaires manuscrits européen (XVIe-XVIIIe siècles): forme, contenu, contexte de réalisation et vocations, Paris, 2003, pp. 59-74.

S. Di Matteo, Palermo, storia della città dalle origini ad oggi, Palermo, 2002.

L. Dufour, Atlante storico della Sicilia: le città costiere nella cartografia manoscritta, 1500-1823, Palermo, 1992.

V. Favarò, "La Sicilia, fortezza del Mediterraneo", in Mediterranea. Richerche storiche, 1 (2004), pp. 31-48.

R. Guccione, "Il duca di Maqueda, promotore degli studi in Sicilia", in Archivio storico siciliano, 10 (1960), pp. 223-237.

H. Koenigsberger, La práctica del Imperio, Madrid 1989.

D. Ligresti, "Centri di potere urbano e monarchia ispanica nella Sicilia de XV-XVI secolo", in J. Martínez Millán and M. Rivero Rodríguez (coords.), Centros de poder italianos en la Monarquía Hispánica (siglos XV-XVIII), Madrid 2010, pp. 287-330.

R. Magdaleno, Papeles de Estado, Sicilia: virreinato español, Valladolid, 1951.

V. Manfrè, "La Sicilia de los cartógrafos: vistas, mapas y corografías en la Edad Moderna", in Anales de Historia del Arte, 23 (2013), pp. 79-94.

M. P. Mesa, "Sicilia en la estrategia defensiva del Mediterráneo (1665-1675)", in P. Sanz Camañes (coord.), Tiempo de cambios: guerra, diplomacia y política internacional de la Monarquía Hispánica (1648-1670), Madrid, 2012, pp. 387-414.

M. R. Nobile, "La Descrittione del Regno di Sicilia, un antico manoscritto inedito riscoperto a Torino", in Kalós. Arte in Sicilia, 3/4 (1991), pp. 4-11.

M. Scarlata, L'opera di Camillo Camiliani, Rome, 1993.

R. Vargas-Hidalgo, Guerra y diplomacia en el Mediterráneo: correspondencia inédita de Felipe II con Andrea Doria y Juan Andrea Doria, Madrid 2002.

M. Vesco, "La Sicilia di Filippo III in un discorso militare occultato: uomini, città territorio", in J. F. Forniés Casals and P. Numhauser (eds.), Escrituras silenciadas. El paisaje como historiografía, Alcalá de Henares 2013, pp. 395-409.

Notes

1. T. Spannocchi, Descripción de las marinas de todo el Reino de Sicilia. Con otras importantes declaraciones notadas por el Caballero Tiburcio Spanoqui, del Ábito de San Juan Gentilhombre de la Casa de su Majestad. Dirigido al Principe don Felipe Nuestro Senior en el anio de MDXCVI, Biblioteca Nacional de España (BNE), Ms. 788. A. Cámara, "Chrorografie et fortification. Spannocchi au service de la monarchie spagnole", in I. Warmoes (coord.), Atlas militaires manuscrits européen (XVIe-XVIIIe siècles): forme, contenu, contexte de réalisation et vocations, Paris, 2003, pp. 59-74. Both the texts from the royal engineer Tiburzio Spannocchi and those from the engineer Camilo Camiliani in the 16th century are the most relevant ones on the descriptive knowledge of early modern Sicily. M. Scarlata, L'opera di Camillo Camiliani, Rome, 1993.

2. M. R. Nobile, "La Descrittione del Regno di Sicilia, un antico manoscritto inedito riscoperto a Torino", in Kalós. Arte in Sicilia, 3/4 (1991), pp. 4-11.

3. V. Manfrè, "La Sicilia de los cartógrafos: vistas, mapas y corografías en la Edad Moderna", in Anales de Historia del Arte, 23 (2013), pp. 79-94. From the same author, we must mention her PhD dissertation, to be defended in the near future. It will present a full analysis of the descriptions of the Kingdom of Sicily: uses, contents, goals and artistic value.

4. See Annex 1. Unpublished Descriptions of Sicily.

5. Biblioteca Nacional de Catalunya (BNC), Ms. 1034, ff. 99r.-126v. Recull miscel·lani de textos historiogràfics sobre Sicília, s. XIV. This text includes copies of several texts from the 14th and 15th centuries' Sicily. It includes the chronicle of Sicily by G. Malaterra and a 40 page description of the island. Considering that Simone da Lentini only transcribed the work of Malaterra and such description cannot be attributed to Lentini for chronological reasons, it is not possible to determine who the author is. Plus, Lentini left no indications towards the authorship of the text.

6. Biblioteca General de Palacio (BGP), MC/688, ff. 5r.-150v. Descritione della Fellicissima Città di Palermo: Oue si vede sommariamente la fecondità della sua campagna, il sito, Grandeza et Bellezza della mesima Città, in che consiste la sua fortificatione e la maniera che si governa /discritta da Gasparo Reggio gentil uomo della medesima Città , 10 de febrero de1599.

7. BNE, Ms.19575, ff. 307r.-347v. Colección de varios manuscritos útiles, curiosos y eruditos recopilados por Tomás Fernández y Prieto, 1791. Bernabé de Cepeda was the pseudonym of the clergyman and journalist Juan Martínez Salafranca. He was a protégé of Philip V and by 1734 he had already published his Descripción histórica y geographica antigua y moderna del Reyno de Nápoles. He also meant to do something similar dedicated to Sicily. However, the book was never published.

8. Regarding Milan and Naples, we must mention, for example: C.G. Cavazzi della Somaglia, Nuova Descrittione dello stato di Milano, Milano 1665; Scipione Mazzella, Descrittione del Regno di Napoli nella quale s'ha piena contezza, così del sito d'esso [...], Naples, 1601.

9. These descriptions and atlases are a Sicilian traditional product, especially if we compare Sicily with other territories from the monarchy such as Naples and Milan. That is why they are so important in form and content.

10. In its first page there is the correspondent dedicatory which precedes a sonnet dedicated to the viceroy duke of Maqueda (1598-1601), topped by a delicate filigree (f.2r.)

11. M. Vesco, "La Sicilia di Filippo III in un discorso militare occultato: uomini, città territorio", in J. F. Forniés Casals and P. Numhauser (eds.), Escrituras silenciadas. El paisaje como historiografía, Alcalá de Henares 2013, pp. 395-409.

12. Despite the destruction of a considerable large number of documents during WW II, in collections such as "Secretaria Antiga", there are over 6.000 volumes on the administration of the Kingdom of Sicily during the Habsburg period.

13. In the section "Papeles de Estado, Sicilia" we can find all the correspondence between the court of Palermo and the court in Madrid. All this information can be complemented thanks to the registries in "Secretarias Provinciales" from Italian territories. For a complete list: R. Magdaleno, Papeles de Estado, Sicilia: virreinato español, Valladolid 1951.

14. N. Aricò, Atlante di città e fortezze del Regno di Sicilia, edizione critica di due codici che si conservano presso la Biblioteca Nazionale di di Madrid (Atlante di città e fortezze del regno di Sicilia), Mesina, 1992. Besides the text, the Atlante included a series of maps about the display of the fortresses across the southern coastline.

15. BGP, DI/ II/310_A, ff. 1r-126v.

16. Di Reggio mentioned, among others, the King Ferdinand II of Aragon and the details of his administration of the great Mediterranean island.

17. There was also a poem dedicated to the Saint Nympha, one of the four patronesses of Palermo by the end of the 16th century. In it, the poet presumes from his Sicilian identity. Biblioteca centrale della Regione siciliana (BCRG), MISC. A.390.7, f. 1r.

18. D. Ligresti, "Centri di potere urbano e monarchia ispanica nella Sicilia de XV-XVI secolo", in J. Martínez Millán and M. Rivero Rodríguez (coords.), Centros de poder italianos en la Monarquía Hispánica (siglos XV-XVIII), Madrid 2010, pp. 287-330.

19. V. Favarò, "La Sicilia, fortezza del Mediterraneo", in Mediterranea. Richerche storiche, 1 (2004), pp. 31-48.

20. M. P. Mesa, "Sicilia en la estrategia defensiva del Mediterráneo (1665-1675)", in P. Sanz Camañes (coord.), Tiempo de cambios: guerra, diplomacia y política internacional de la Monarquía Hispánica (1648-1670), Madrid, 2012, pp. 387-414.

21. The death of the count of Olivares in 1595 required an interim presidency until a new viceroy was appointed. Giovanni III Ventimiglia was the chosen one (1595-1598). Philip III named the duke of Maqueda as his new alter ego in 1596. However, his arrival in Palermo was only in 18th April 1598 due to some problems the ships of Andrea Doria suffered. During the time gap, the marquis obeyed to the orders the duke sent from Alicante. R. Vargas-Hidalgo, Guerra y diplomacia en el Mediterráneo: correspondencia inédita de Felipe II con Andrea Doria y Juan Andrea Doria, Madrid 2002, pp. 85-87.

22. BGP, MC/688, ff. 6r.

23. L. Dufour, Atlante storico della Sicilia: le città costiere nella cartografia manoscritta, 1500-1823, Palermo, 1992, p. 8.

24. BGP, MC/688, f. 35v.

25. Idem, f. 36v.

26. It was the smallest unit of the monetary system in Sicily. The taxes, named "gabela", over certain goods were regulated through a quantity of taris. H. Koenigsberger, La práctica del Imperio, Madrid 1989, p. 62. Finally, the duke considered the measure and issued in 1600 a pragmatic to enable it.

27. BGP, MC/688, f. 52r.

28. The Quartieri were the different neighborhoods in which the city was divided. From the moment the Strata Nuova was opened, they were four: l'Albegheria, la Kalsa, il Capo and la Loggia.