1 - 1957/1980 : Baroque and Classicism

In 1957, Victor-Lucien Tapié, a Professor at the Sorbonne in Paris, published a book entitled "Baroque et classicisme". In his introduction, he imagined his reader on the terrace of the Palace of Versailles, on a beautiful autumn afternoon. This reader is French (and a French man, of course) - a cultured, catholic man immediately and spontaneously in contact with the harmonious beauty of Versailles Classicism. This is the very reader to whom he wanted to explain baroque, 70 years after the publication of Heinrich Wölfflin's famous book on Baroque and Renaissance (Renaissance und Barock. Untersuchung über Wesen und Entstehung des Barockstils in Italien) in which the author identified a certain number of formal features likely to characterize Baroque art.

It must be noticed that beyond the diversity of their approaches, the famous Swiss critic, the French Professor, and between, Benedetto Croce, did grasp Baroque only in the notional couple it forms with "classic", whether classic preceded baroque as in the case of Italian Renaissance, or followed it as in the French case.

Tapié's book was widely read and taught. It was reprinted at least twice: in 1972, in 1980. The 1980 edition - a paperback edition - was published with a preface written by Marc Fumaroli who, at that time, was also Professor at the Sorbonne. This preface started with a long quotation that settled as the source of the reflection on Baroque, a figure highly different from what the cultured and catholic Tapié did, since it was the figure of a woman: Mme Gervaisais, a character in a 19th century novel written by the Goncourt Brothers. In the exuberant setting of the Gesù church in Roma, Mrs Gervaisais experiences the violence of something made of piety and sensuality "mingling at the same time a boudoir mystery to the holy of Holies mystery". In short, as Nietzsche wrote about Wagner, this is an art for the nerves; we could add: an art for the nerves of women, "a kind of blurred feminine complicity". Once this psychological framework settled, Fumaroli set about the German origin and the German dimension of the critical concept of baroque (the Barockbegriff), by reconstructing approximately its history, related in his opinion to the Germanic nationalist romanticism, that led to Spengler and to the Decline of the West, to the conservative revolution, (also) continued in that respect by nazism. Hopefully,added Fumaroli, the Barockbegriff offensive was held back by the intellectual elite and the French national genius full of so many "grands siècles". Thus, in the 1960s-1970s, taste for baroque is interpreted as inappropriate and distasteful -- as a political desease. This is a "phenomenon characteristic of a generation "who took part in the events of May 1968 in France, favoured in young minds by sweet intercrossings between academic science and novelistic fancy, between philosophy-literature and delusions, between the Ecole des Annales and a sentimental tourism". In addition, he showed Tapié - who died in the meantime - as a critic, though he was undoubtedly one of the few who introduced in France the word "baroque" and the interest for baroque.

Recently, our colleague Harmut Stenzel wrote an answer to Fumaroli's polemical reasoning. First, he shows that German debates about the notion of Baroque did concern more accurately the intellectually franzied period of the Weimar Republic than the 2nd or the 3rd Reich. He provides us with a purely historical demonstration that wipes out part of Fumaroli's assertions. Next, Stenzel relocates the discussions about Baroque within the history of German literary criticism, and especially within the so-called "Germanistik". As a result, it appears that the notion of Baroque was indeed an intellectual weapon against classicism. However it was not "classicism" as a period of Italian, French or German intellectual, literary or artistic period but "classicism" as a critical value built up from the ideas of harmony and transhistoricity of what is beautiful and good. The notion of baroque as a critical notion is clearly opposite to cultural hierarchies; it shows up an historical relativism of the aesthetic value and thus allows to historicize (artistic) works. In addition, the theoretical stakes of the notion of baroque were powerfully underlined by Walter Benjamin, especially in his Origins of the German Tragic drama. In that respect, Stenzel writes:

"The anti-classicist function of the notion of 'baroque", as pointing out a torn style as well as (pointing out) a time in crisis remains vivid in research too. The most famous example is provided by Walter Benjamin in the 1920s, when he outlined a definition of baroque in his analysis of "baroque" tragic drama. At the core of his analysis, Benjamin settled the aesthetic notion of "fragment" that he considered as a fundamental characteristic of "baroque"; and this allowed him to designate baroque as the "sovereign counterpart of classicism" ("Soveränes Gegenspiel der Klassik"). Through the notion of "baroque" and with an intention that might already be called "deconstructivist", Walter Benjamin worked out an understanding of the texts that consider them as "ruins" - as so many expressions of the impossibility to reach any ideological or aesthetical coherence.

In this theoretical debate, the ideological consequences are really heavy: on the one hand, there is some faith in permanent aesthetic values capable of going through the ages, and then, capable of founding an implicit theory of value which legitimizes totalizing and trans-historical hierarchies. On the other hand, there is an historical relativism of value that considers artistic, architectural or literary works as remnants of the thoughts and practices that produced them - remnants that can be understood as processes of contextualization which require to separate past and present while considering that the productions of the past are likely to go on producing effects in present time though as past effects and not as a tradition that would have remained intact as a kind of inexhaustible source. Moreover, following Benjamin's tracks also lead to methodological consequences: what is baroque is not only the object of the past but also the theoretical attitude that allows to grasp this object as a "ruin", as a fragment, out of any harmonious totality.

2. The political fight of anti-baroque against Neoclassicism

On July 19, 1940, Walter Benjamin was hunted down by the nazis; and while he tried to reach an exiled place, he wrote his last letter to Gretel Adorno. He mentioned to her "I have brought away only one book: the Memoirs of the cardinal de Retz. Thus, when I am alone in my room, I can resort to the Grand-Siècle".

What does it mean " resorting to the Grand-Siècle" in the despairing weeks of summer 1940? Of course we know that the numerous and continuous constructions of a "Grand-Siècle" have thoroughly imprinted on the history of scholarship, on the history of literary critique as well as on the history of education or of the political life. However, what these constructions may become when "the very moment of danger" is the specific context of their evocation? At the beginning of 1940, Walter Benjamin wrote "Working as an Historian does not mean knowing 'how things did really happened'; it means grasping a souvenir at it arises as the very moment of the danger, [it means] holding back the image of the past that presents itself unexpectedly to the historical subject at the very moment of danger".

This letter was written a few weeks before he failed to cross the Spanish borders, and as a consequence of this failure, he committed suicide.

At the same time and in front of the same danger, Paul Benichou put an end to his 1st book and masterpiece entitled Morales du Grand Siècle. At the end of his book, he made a point of mentioning "Bergerac, August 1940". Benichou was born in 1908 in French Algeria. After his studies at the Ecole Normale Supérieure, he obtained his agrégation in 1930, then becoming a secondary teacher. He started to work on his Morales du Grand siècle in 1935. He put an end to his book after his demobilization from the defeated French army and before he was dismissed from teaching as a result of the anti-Jewish laws of Vichy government. The book was only published in 1948. Then the mention "Bergerac, August 1940" explicitly underline a time and a place that must be kept in mind while reading his conclusion of the book: "going through what was thought in the past makes only sense and virtue in comparison to the present and future". The last lines of his conclusion called out to a dark present and a really uncertain future in a touch of optimism based on the steadiness of his argument: "The Grand siècle that is too often admired or fought for the mere constraining powers it contains, gives already evidence in favour of a conception of civilized man, that has continuously grown stronger and wider afterwards, that our time would pretend to reject in vain, and that a future probably closer than it may seem will have to rescue and to go deeper and deeper".

According to Benichou, the long-term history of humanity is then characterized by the fighting contrary forces of human desire against the regressive constraints of poverty. In his writing it became the wide environment of his experience of thought within danger. The French 17th century (the "grand siècle") represents a specific moment in the history of this confrontation - a moment that makes sense in a longer history. The ethics that the study of literature allows to restore in its own thinking and its own words/ vocabulary, appears to be the most expressive place of this ideological, political and social confrontation. A whole series of consequences result from this vision of history and this resort to literature. The most striking consequence in the environment of 1940 is the connection made between the current event and a long-term history that cannot explain it but that can provide it with some depth. And as this long-term history is itself caught through an actualizing process that captures and expresses its age-old power, it points out its orientation and its potentialities. At the end, 1940 and the Grand-Siecle are face to face, out of any rhetorical performance.

Moreover, the most explicit parallels are expounded in footnotes. As an example, in the chapter dealing with Molière, when he evoked the long-term presence of the "esprit courtois" and the re-interpretations of this "esprit courtois" favoured by the monarchy (that transformed it without never abolishing it), Benichou wrote in a footnote:

"This is how the old monarchy mostly differed from the contemporary dictatorships arisen from a regression toward poverty. The architecture, arts, paintings of that old times expressed an ideal of blooming (which was all the more freely expressed that it only concerned a minority of people). The contemporary dictatorships arisen from a relative shrinking of general welfare rather than from its expansion are more worried by bulk movements. They turned necessity into a virtue, took on the Spartan attitude, condemned pleasure regressively and did acknowledged only war magnificence as the mirror of any poverty."

It can be seen here how politics is embedded into Ethics and how insistently the supposed greatness of the Grand-siècle refers to the power of some human energy which will be embodied in other figures the following century. And this greatness of the Grand-siècle has nothing to do with the so-called militarized "greatness" of dictatorships (which is a contemporary avatar of poverty). Of course, this kind of position did not at all get rid of the political dimension of the moral analysis; it was a response to other visions of the 17th century and its literature, visions that highly admired authoritarian regimes. We can mention, for example, the neo-classicis

m emphasized by Charles Maurras, an active royalist writer in the movement Action Française. We can also mention Robert Brasillac, one of Maurras' fascist follower who was executed in 1945. In such a perspective, literary critique holds some political responsibility.

Benichou tried to save a humanistic vision of the French 17th century, in opposition to other scholars who only wanted to preserve the taste of this century for authority and discipline, producing dangerous equivocations that became particularly harsh at a time when authority, order and strength were settled as the prime values of dictatorships.

The conclusion of the Morales du grand siècle, entitled "reflections on classical humanism" is dedicated to explain and clarify this position. Benichou strongly championed an idea of continuity of the "three grand siècles" (the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries) characterized by (I quote) "the development of modern humanism" and "the fundamental rehabilitation of human desire"; the disruption between a 17th century "of order and discipline" and a 18th century "of subversion and utopia" as settled by those who wanted to "hold in contempt everything that had inspired the French Revolution, without denying as a whole a tradition of humanism that couldn't be separate from the monarchistic civilization itself". What was at stake in acknowledging a continuous progress from Renaissance to Revolution, was the ability to provide historical and moral resources allowing to hold out against the attempts to enlist the 17th century in the regressive ideologies that celebrate rough strength, the intrinsic value of constraint and repressing desire.

"Bergerac, August 1940" reminds the roughness and greatness of what is at stake.

Twenty seven years later, in 1967, a lively short book entitled Le Mirage baroque (The baroque mirage) wrote by Pierre Charpentrat, a historian of art and architecture, proposed a satiric anthropology of the baroque fashion. However, during the 2nd World War, there was no baroque fashion at all: when the Cahiers du Rhône, published in Geneva, propose a series of papers on baroque, it aimed at sustaining the spirit of resistance of French intellectuals and at providing them with arguments against the neo-classicism of collaborationist intellectuals.

3 - A fruitful historiographical debate thanks to Pierre Charpentrat

Pierre Charpentrat was born in 1921 and died in 1977. As an historian of art, specialist of baroque, he was very careful about the intellectual tools used in art history. His approach consisted in producing some historical knowledge by a paradoxical way: he associated scholarship (i.e. reconstructing the points of view of both producers and users of baroque monuments) to a singular and actual experience in the present, of the same objects. His approach was rooted in refusal. Charpentrat came down strongly the history of art as it was dominantly taught at the university and that he called "Hegelian". Using this adjective allowed him to denounce a history of styles that substantialized its objects to organize more easily their dialectical succession: as a consequence of such globalizing history of styles, works of art stand out of any historicization. In the case of baroque, this movement was accompanied by a rather underhand phenomenon by which stylistic concepts circulated from one scholar discipline to another. This is how categories used in architecture and that were more descriptive than interpretative were used metaphorically by the "literary baroque" to characterize writing practices; and then, these metaphorized concepts went back into their original discipline and more generally into the history of art, however weighed down with images and with some "spirit of the time" that they (these images) expressed and caught as unit, coherence and as identity.

This critical analysis proposed by Pierre Charpentrat might also be an answer to the work of Victor-Lucien Tapié and (of) other historians of art and literature who postulated the existence of a "baroque mentality" likely to explain what forms meant while these very forms did characterize a period of time when people share the same conception of the world and the same imaginary precisely apprehended by these large categories as Metamorphosis, Movement (both with capital M) or Ostentation (with capital O).

Such an history of mentalities tended to put aside social differences, specific sharings as well as pecularities or confrontations, since everybody of the same period and at the same place was supposed to share the same "baroque mentality". In several papers published in the French Journal the Annales ESC (Economies, Sociétés, Civilisations), Pierre Francastel a Marxist historian of art get involved in a sharp controversy with Tapié. It seems that this debate aimed at providing efficient definitions and at settling steady limits to both canonical notions, classicism and baroque, that Tapié used either as compared, opposed or associated. However, beyond their deep differences both scholars thereby compare comprehensive forms and writing practices in the very spirit of their time. Tapié tried to turn from "the general characters of a society" to "the style favoured by this society" (as if, Francastel answered him, a nation was able to choose a style as one chooses a suit or a horse) and was led to draw the conclusion that baroque has been successful in the most rural and feudal regions of Europe. On the other hand, though he was attached to an interpretation in terms of "way of thinking and acting", Francastel strengthened the opposition between baroque and classic. In his opinion, classicism was a revolutionary form of modern thinking in the 17th century; as such it expanded in the countries where there was high social mobility, while baroque developed in places and areas where there was social stability and social unity.

Thus, the interest for baroque led to a renewed and ever-increasing exaltation of national classicism while, in principle, the issue was to put limits to its domination.

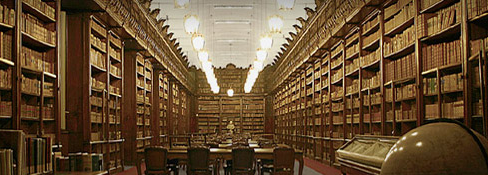

In opposition to the history of mentalities practiced by Tapié, Pierre Charpentrat held the position of witness of the phenomena that he identified in the past; to a scholar reconstruction of the past (of the projects and functioning described in the archives), he associated an experience of reception in order to restore as object of knowledge the unity of effects that characterized the baroque place in its project as in its actual functioning. This is (the place) where historical knowledge meets the subjective experience of what travelled down the ages. So, Pierre Charpentrat claimed subtly to be an historian of the porous border between knowledge and experience. The fact remains nonetheless that for him, the term "baroque" acquires an historical meaning only in the evocation and analysis of the "baroque space" conceived as the result of a project, a construction, as what still allows an experience of reception - a space where present meets past in the effective actualisation of a vision. This is the reason why if medieval and renaissance churches can be "deconstructed" into several distinct volumes, the space of a baroque church is "homogeneous and indivisible". This does not allow to work out an analogy with certain characteristics of "ideas" or "mentalities" of that period, however it allows to understand how this space was conceived to express and enact theology and pastorale, at a very specific moment of their history.

The unified baroque space is plainly filled by constant movement: (I quote) "vacuum is necessarily ignored by a space undivided into compartments". The feeling of some vacuum that would have been forgotten by the architect or the decorator would threatened the whole functioning of the building - it would amount to deny a serious slip of the tongue. Thus, it was required to chase the "bubbles of vacuum" through the decoration and to burst these bubbles one after another with "the sword held up by an archangel, the rays of an asymmetrical "glory", the unexpected growth of an exotic plant on a transom or a confessional, the leg of a seraph hanging down of a pulpit, so that space would amalgamate around a backbone made of virtual trajectories". When the eye wanders around, its very circuit creates the "mysterious unity wished by orthodoxy". So (I quote) "contemplation is movement and reinforces the cohesion of space". And the spectator, handled by effects that brought him into the subjection of an orthodoxy, becomes an actor who plays the part chosen for him by the whole device. Such is the real meaning of baroque theatricality. It is not an indication/ it doesn't mean that "life is a theatre"; it results from a persuading action in which the addressee of its effects is considered as a spectator likely to become the actor of his own adhesion. In this enactment, frescos in trompe-l'oeil are an essential instrument. They accompany, sometimes dissimulate or transcend the most determining choices of the architect about the structure of the building. The most spectacular and noblest trompe-l'oeil is the zenithal trompe-l'oeil that can be found in baroque palaces and churches.

In churches, it allows the representation of an opening towards the infinite sky, to which the glance is vertiginously led. Of course these are pretended enactments (simulacre in French) - nobody really believes that the ceiling is opened toward the sky. These enactments perform an essential theological and pastoral mission. They show what cannot be express or figurate.

[The zenithal trompe-l'oeil] helped the catholicism after the Concile of Trent to get out of a serious contradiction: striving to put a fierce and meticulous strategy of visualization at the service of Transcendency. By making feel a Presence which is Absence at the same time, by indicating imperiously a Beyond that no one can represent, trompe-l'oeil avoids both idolatric representation and abstraction (fatal enemy of the Counter-Reform) [...]. Its ultimate tour de force consists in annexing the Invisible to a world of glance, on behalf of a theology.

*

At first sight, the book written by Victor-Lucien Tapié, Baroque et Classicisme, appears as an example of academic debate, maybe a little bit vain and surely unlikely to go out of the academic world. However, the toughening of the anti-baroque positions in Marc Fumaroli's preface written more than twenty years after the first publication, is an invitation to contextualize the academic positions in longer-term history where scholar controversies about the interpretation of the past acquire a different tonality. The history of the historiographical choices as well as the history of the disciplines of knowledge appear to be entrusted with stakes which may go unnoticed in a first place. Indeed, the 17th century which is the century of baroque and classicism in France appear to be a complete different world from the present world of the conflicts of the contemporary history. Nevertheless, the names of Walter Benjamin and Paul Bénichou, the topicality in which their appeal to the "grand-siècle" is caught, the theoretical strength of their analyses considered as the political effects of certain academic positions, all this displays the ideological chasm which can grow deeper in certain tragic circumstances between opposite scholar notions often unthinkingly handled by art and literary critic.

This historical gravity leads us to assess what is at stake in an historiographical breach as Pierre Charpentrat produced. While he broke both with the tautology establishing facts from categories and categories from the same facts and with the history of mentalities that unifies the past to separate it more easily from the present, Charpentrat stated the necessity to contextualize thoroughly the traces of the past and (the necessity) to question the traces of a past experience surviving in the present.

And thus, here is what can seen: the fight of men of the past to show and pass on what cannot be represented and to impose their interpretation, as well as the modalities of the presence of the past in the experience of its perception.

Then, baroque becomes an instrument to know something else than itself - an instrument to think and consider at the same time and all together the irreducible singularity of the thinking actions of the men of the past and their long-lasting effects.